Gilberto López y Rivas

In the context of the multiple forms of neoliberal violence that prevail in the global and national sphere, in the forum: From the horror of war to resistance for life, convened for the emergency situation that prevails in the territories of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, I presented, at the panel on violence, the deepening of the counterinsurgency war strategy through the action of various armed actors. On the one hand, paramilitary groups, such as the Orcao, which proliferate their attacks against Zapatista communities, and, on the other hand, the growing presence throughout Chiapas of organized crime cartels, within the framework of a process of militarization and militarism continued by the current government.

The paramilitary action has lasted for several decades, based on a counter-guerrilla military tactic known as “anvil and hammer,” according to which the Army and police institutions adopt the passive function of containment forces (anvil), which allow them to carry out, in this case, the active function of harassment of the paramilitary groups (hammer) against the EZLN and its support bases. Since the outbreak of the Zapatista rebellion, the paramilitary groups have been reorganized.

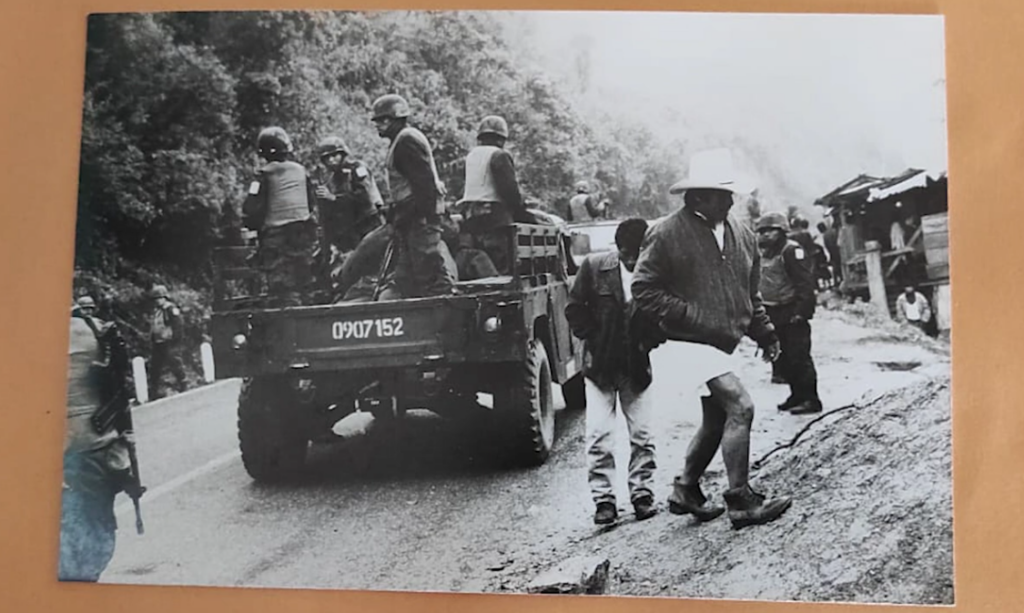

Hence, there is a crucial element in the counterinsurgency strategy: the action of paramilitaries who are used in tasks that the armed forces prefer not to carry out directly. This was a tactic used in Guatemala, although there the army directly played the fundamental role in the genocide against the indigenous people. In the Guatemalan conflict, which worsened in the 1960s, we find what could be the blueprint for paramilitarization and militarization in Central America and Mexico. Far-right groups that presented themselves as autonomous, but were attached to the intelligence section (G-2) of the Guatemalan army, civilian self-defense patrols, which in principle were forcibly recruited by the army and played a role in massacres and military control of communities; scorched earth practices during the government of Efraín Ríos Mont (brought to justice for genocide) in the 80’s, which were nothing more than the bombing of communities with the population inside. These are all examples of an experience that, over 36 years, left over 100 thousand dead, 40 thousand disappeared and 50 thousand refugees abroad, many in Mexico, and one million displaced to other parts of the country, 600 collective massacres and an accumulated experience of repression that goes beyond the borders of Guatemala—for example, the Kaibiles, a particularly bloodthirsty corps of its army, which trains the Mexican armed forces.

The state link provides a fundamental element for a definition of the Latin American experience: the paramilitary groups are those with military organization, equipment and training, to which the state delegates missions that the armed forces cannot openly carry out, without this implying that they recognize their existence as part of the monopoly of state violence. Paramilitary groups are illegal and unpunished because it suits the interests of the State. The paramilitary consists, then, in the illegal and unpunished practice of State violence and in the concealment of the origin of that violence. Especially in the cases of Chiapas, Guerrero and Oaxaca, paramilitarism serves the purposes of counterinsurgency, destroying or severely deteriorating the social fabric of communities and social organizations in resistance. It behaves in a variety of ways: It attacks social service providers, causing conditions of expulsion and displacement of indigenous and peasant communities; it forms alliances with civil authorities; it harasses through the actions of corrupt judges and judicial police; it infiltrates religious associations, carrying out intelligence work; it raises developmentalist dilemmas that cause clientelism and environmental deterioration, such as Sembrando Vida, and places communities that refuse to follow the logic of capital as enemies of development; and, above all, creates or increases the spiral of violence in the communities, imposing violence as a way of life. Also the insertion in the communities of Chiapas, and other states of the country, of phenomena such as prostitution, alcohol consumption, domestic violence, are the result of the presence of the Army, as documented by Juan Balboa since 1997 ( La Jornada, 27/1/97).

This is only part of the broad spectrum war that is being waged in Chiapas (and in other states of the country), and which we denounced in this forum, with the purpose of breaking the media blackout and the denialism of the Mexican State that encourages impunity.

Original text published in La Jornada on August 4th, 2023. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/08/04/opinion/019a2pol

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.