Ángeles Máriscal

The communities of Escobillar, Sonora and Monte Ordóñez, in the municipality of Amatenango de la Frontera, also abandoned their houses and land. Before leaving, they opened their corrals so that the cows and oxen could fetch water and food on their own, they let their backyard animals loose. They can’t even take the dogs with them, and for miles around it is already a battle zone between the drug cartels.

Among the paddocks there is a long line of people with serious faces. They walk carrying some of their belongings in bags. They see no prospect for a prompt return.

……

Two weeks earlier, members of that which presents itself as “the good cartel,” the Sinaloa Cartel (CDS), arrived in Monte Ordoñez. This region of Amatenango de la Frontera is just a few kilometers from the border with Guatemala, at an apex from where you can reach Frontera Comalapa, La Grandeza, Bellavista and Siltepec, the municipalities of the Chiapas highlands that are now a zone of conflict between cartels.

They told them “we are not going to charge you any taxes, we just want you to cut down some trees on the road.” The peasants of Monte Ordóñez obeyed, in their region the Jalisco Cartel – New Generation (CJNG) and its arm called MAIZ, has been gaining ground with a trail of terror, kidnappings, and disappearances.

When they were cutting down the trees to place them on the road – a strategy to impede the passage of the armed men’s trucks and the army, which often drove in front of them – members of MAIZ arrived, shouted at them, beat them and shot them. Eight of our compañeros were left dead.

The person who told the story said that the bodies were left lying around for several days, “because their families could not go to pick them up… they were left there as an example. That’s why the people said they should all leave the community. They all left.”

Since the beginning of January, confrontations between the two cartels have increased. “All day long we hear gunshots, we people know that at any moment they will arrive, we know that there is no protection, we know about the complicity of the 101st Infantry Battalion of the Mexican Army. We are already praying, praying to God that this does not happen to us,” explained the farmer.

The day after the inhabitants of Monte Ordóñez left, the inhabitants of the Escobillar and Sonora ejidos, also from Amatenango de la Frontera, followed in their footsteps. In total, some 2,000 people joined the already long list of people displaced by the actions of organized crime.

Slaves

“We are forbidden to look up. We can’t turn to look at them. All the time we have to look down, at the ground,” explains a farmer who lives in the area of La Grandeza, a land of paradisiacal landscapes, mountains and intense blue skies, in which a cold wind blows.

The farmer is one of the few in his community who decided not to leave his village. His family did not want to leave, so they agreed to submit to the rules of the cartel that is currently gaining ground in the region where they live.

“What they ask us now is to bring food to the place where they are. Every day we prepare food for about 25 people. They come and tell us: we want this, we want that, don’t bring beans… we have to make it to their liking. Sometimes they are the ones who take the chickens that were left loose in the houses of those who left. We are their slaves.”

The farmer explains that even his house can hear the gunshots of the clashes. I ask him who are the ones in the line of fire, with the guns. Who are the people who are fighting? Are they young people from the area? Are they people from the region?

He answers that almost all are people from abroad, some with accents from other regions of Mexico, but the majority “are people brought from Guatemala, they are Kaibiles1,” he explains, although he is not certain of this. He only emphasizes that, because of their accent, because of their way of speaking, they are not Mexicans. Some other testimonies detail that, among the attack forces of the cartels, there are young Central Americans, “they are people of the migrants, of the maras2,” as they call them.

Some 200 kilometers to the north, in the area of the rivers that lead to the dam, another of the cartels has hegemony, the CDS. There, in one of the towns that overlooks the Angostura dam, the subjugation of the population began at the end of 2021, with the disappearance and assassination of community leaders and ejido authorities.

Now, more than two years later, now that the population has given up asking for help from the authorities, those who decided to stay in the region are also living at the service of the cartel. In this community there is a Mexican Army detachment just 40 meters from the center of town. That doesn’t change their situation.

Last Monday,” one of the inhabitants explained to me, “the cartel gathered the people together and told them: you have to endure one more year, under the new government they will start attacking our opponents and it will be calmer.

Endure what? I ask him. “It’s just that the situation got worse, before they asked us to go to blockade as needed, but now it’s shifts three days a week for 24 hours each shift.”

This refers to the blockades placed by the civilian population at the entrances to towns, which serve as a barrier to prevent the passage of the Mexican Army or the opposing cartel. Both cartels, the CDS and the CJNG, use this strategy of using the population as a human shield.

In his village, the farmer tells me, “we only live for the cartel, we can no longer harvest, life here is over, now we have to work 24-hour shifts three days a week, not only in the village, but now they take us to other places further away.”

“The people are already tired, they want to leave. That’s why they gathered us together, they told us that whoever leaves loses their houses, their ranches, their land. They told us to hold out for a year until the government changes, that’s what they told us, that when the new governments come in they will give them protection and attack their rivals.”

The peasants, those who stay and those who flee, cling to any glimmer of hope that the current situation will change in this region of Chiapas.

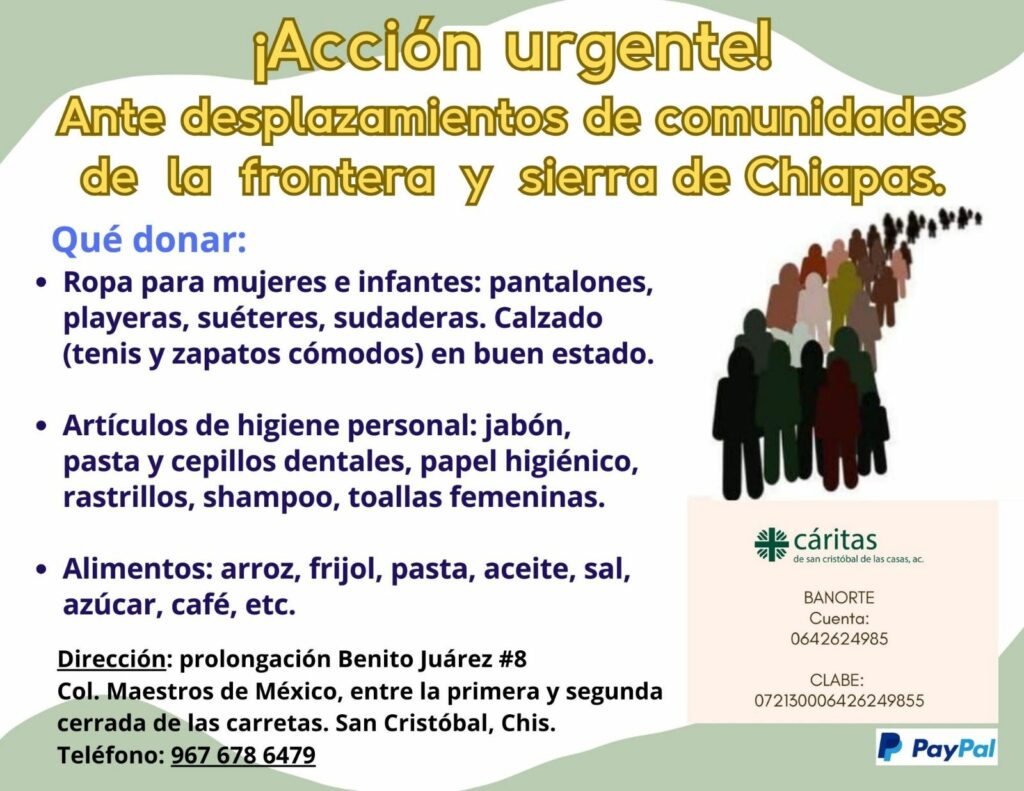

If you want to donate to these families in crisis, and cannot donate directly through your bank account, you can donate to our emergency fund with the recipient name Chicomuselo and email direccion1@ceps.org.mx.

Original article by Ángeles Máriscal published in Chiapas Paralelo on February 1st, 2024. https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2024/02/continua-exodo-en-la-sierra-de-chiapas-somos-esclavos-ya-estamos-a-pura-voluntad-de-dios/

Thumbnail image taken from video by Ángeles Máriscal.

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.

Footnotes

- The Kaibiles are a special operations wing of the Armed Forces of Guatemala. They specialize in jungle warfare tactics and counter-insurgency operations. They are best known for their brutal tactics and acts of barbarism in the Guatemalan Civil War.

- Maras refers to Latin American gangs from the U.S. that have spread into Central America