“We know that we are not alone in this journey. How many compañeros and compañeros have come to these lands of ours to share their knowledge, to teach us and for us to teach them, how much they have dedicated their whole lives to share our word, our thinking, to look for ways to support us in this struggle that belongs to all of us,” Manuel shares, the emotion so visible on his young face. “Thanks to this support we can continue to build our schools and clinics, develop materials, have access to medical equipment that allows us to care for our sick…Despite all the vision, without that support, we could not have carried on. It is beautiful that there are people who share this vision of equality in the world and that is why, with all the strength we have, we call on them to continue building together.”

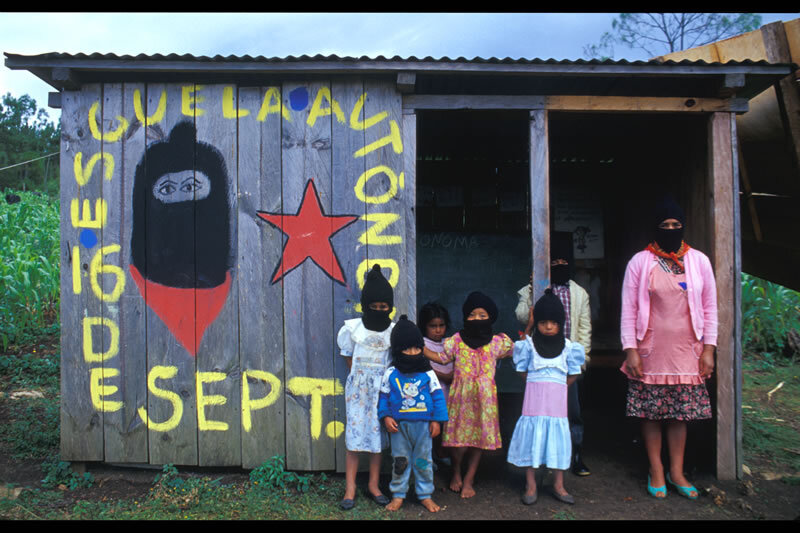

“At the annual meeting of the education promoters there were hundreds of us, … really hundreds,” says Manuel, who is only 23 years old and has been serving the community as an education promoter for seven years. “You live in your community taking care of the children in school and you don’t even realize how many education promoters there really are. And there we were, all together, getting to know each other, sharing our stories and experiences at different work tables. The young compañeros from the distant zones, some from the hot lands, some from the cold – some from the highlands of Chiapas, compañeros who never ate rabbit in mole, and those of us who’d never had yucca and chicken with panela and cinnamon. The music they listen to and instruments they play, dances and songs…we are all so different and yet…”

For the history that we write in our languages, the journey of the original peoples, the shared history of discrimination, humiliation, poverty, resistance and rebellion that our ancestors organized against the colonizer – we are all the same. And then sharing about teaching experiences, fellow educators, many of them very strong and others with more challenges.

There are zones and areas where the primary schools only have 15 students because the rest of the people have party affiliations, because the parents in the communities send their children to the government school. They prefer to be given things, clothes, and a few boards for construction, books from which to learn the official history —the history of the great Spanish heroes who came to liberate us from evil. In government schools this is the history that children learn. They do not know that the native peoples had such a great history and impressive economic, cultural and scientific advances before the arrival of the Spaniards. They think that all knowledge came with the Europeans. They do not believe they are capable, they feel worse than the mestizos because they are told all the time – ‘you are an ignorant Indian like your ancestors and that is how you will remain if you are not with us, if you do not learn imperial history, if you do not recognize your place in the world.’

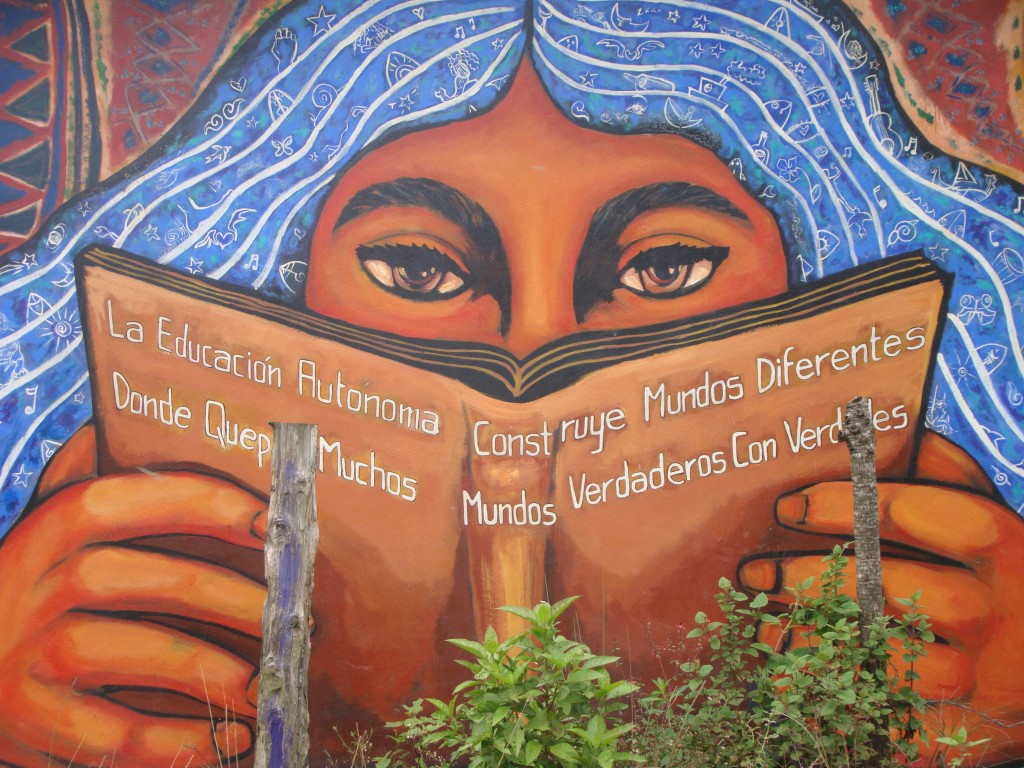

The purpose of our Zapatista education is to teach generations in the practice of autonomy and self-government to preserve our indigenous dignity. Those who come to visit our schools say that our experience is not a model nor does it fit into other pedagogical currents. Because here – literacy means to read the world and transform it. In this sense, the Zapatista school is anti-capitalist and is not governed by the norms of the market that issues titles to be exchanged for money, job titles that define you and enslave you; it is not merchandise because no one pays to learn and no one is charged for teaching; nor is it a mechanism of the State, because each village determines the curricular content to use our knowledge, to develop the collectivity of the countryside, and to promote cooperatives and communal stores. Unlike the global trends in schools that promote the entrepreneurial mentality, merit and self-employment, our education aspires for students and young people to serve their people, and show solidarity – that knowledge does not imply social hierarchy.

Our teaching seeks a more autonomous, active, creative and liberating learning, in which dignity is more important than the commercialization of professional titles. Quality and evaluation criteria related to efficiency and industrial productivity control do not exist in our schools. It is not education to promote the entrepreneurial and individualistic ideology of human capital as a solution to all problems. On the contrary, our proposal builds from the communities in order emancipate ourselves from capitalism and from its four wheels: exploitation, dispossession, repression and contempt. We know that our process of education is still under construction and there are things that we, along with our elders, need to be careful about so as not to go into the bureaucratization and homogenization that is so typical under capitalism.

In government schools they teach young boys to be strong males, males who climb the ladder of ambition and individualism. According to them, men have to demonstrate a patriarchal idea of strength. They want a man who supports the family, who has his wife working at home, a man who does not allow his partner or children freedom of thought. A man who will eventually have a business, an income, and who will only support the family that has to listen to him. This man will grow into a tyrant only to later realize that he will depend on the system because in the end he too is a slave. In our schools we teach the history of the people, how our ancestors were, how they worked the land, how they built the family. Of course, with the arrival of the Spaniards, we too were macho, we wanted what was ours, and control over others. But that changed as a result of the Zapatista movement. There was space to share, to listen. Not that it was easy for us. One of the most beautiful visions we have is to teach our students to open up, to recognize our mistakes as men and women, as a society.

In our towns, parents insist that their children go to school. Children do not always want to go to school, but we know that it is the first portal to understanding the world, where we find ourselves as people and as a community. We understand that we have to change the world, but children have to learn that from a collective vision, from the practices that we live day by day. Not only the ones biased by power.

We are able to have all children from the communities studying I believe because our schools give rise to a gradual learning of freedom and teaches us all to take collective responsibility for the problems of the school and of the people. It encourages parents as they too are part of our constant education and participate in decision-making. It is intercultural and intralingual because students and mentors from different ethnic groups coincide; interethnic teamwork is encouraged where students and mentors teach each other their language and culture.

The classroom has no walls; we learn how to combat the blight in the cornfield or carry out disease prevention campaigns. They (the schools) are self-run because we refuse to receive official support from the state; they are also intersubjective, because the relationship between authorities, villages, and us, as promoters and students, is horizontal. For us it is our struggle against colonialism – our education is decolonial because it pursues social transformation, liberation, and rescues and validates ancestral and community knowledge and ways of life. It is different from the schools with students whose families don’t belong to the movement. They have authorities, they don’t participate in the decisions, and they depend on the government’s materials for what to learn or not. Students in government schools continue being colonized.

Girls at school are the ones who apply themselves the most. I thought it was only like that in my community, but it is not. It’s so nice to see them getting ahead in math, and how beautifully they write. I see some of my neighbors, and they don’t even send girls to school. “What for?” they say. They ask my dad why all of us study and why many want to be educators or health promoters. People who are not in the movement think about other things: starting a business, moving away, getting married for the first time, having children, or having a car.

We talked with other education promoters about how difficult it is for young people to stay in the movement, they have to be very determined, and to truly believe in another world. They all have friends who invite them to work in places outside the community, who invite them to emigrate to work in the United States, to get more money, to be, what they say, better off… but I ask myself, better than what? Here many of us share the land that we sow, and we sow not only our food but we sow our vision, embodied in every movement we make.

Girls who are in school become strong women, women who demand their rights not only in words, but in actions. Women who read, analyze, take care of their families, travel to meetings with other women, build their spaces, have collectives where they build, talk, share, teach. They are leaders who seek men who are on the same path. Partners not husbands.

They are the health promoters who walk from house to house attending patients not only with diagnosis and treatment but also with words, with embraces, and with the strength of the struggle. They are the ones who get up early, sometimes leaving their family to take care of others, they are the ones who tell their partner “today it is your turn to prepare breakfast because I have to see my people, my community, to support my compañerxs in the paths we have chosen.”

Putting all our strength in building education from below, in looking inward and sharing our vision with our comrades is what strengthens us.

In government education we lose who we are, where we come from, the knowledge of our peoples, the ancestral wisdom that we carry in our blood. We know that who we are today is the product of thousands of years of knowledge and this knowledge is the basis for understanding today’s thinking. The history that is being woven today cannot exist without these roots, but we also teach that what is happening in today’s world did not exist before, we teach how capitalism developed and how we indigenous peoples suffer from it. We have to understand that it is global, that it is not unique to our territory, or the country of Mexico. The children have to see the connection between the decisions that are made thousands and thousands of kilometers away from their homes and what they experience here.

And this is what surprises outsiders – the value we give to our ancestors, to be able to develop our knowledge from their practice of autonomy and self-government. Only in this way can we teach —teach literacy to young people in order to transform the terrible things in the world around us.

During the meeting we realized that it is not easy to do so with what is happening around us. They try to divide us as indigenous peoples, we do not participate in what are defined as the rules of the market—the official system that gives titles to create workers in a system that requires exchange of money rather than exchange of knowledge.

Manuel’s smile is contagious. “It is very nice to share with our colleagues what unites us and why we do this work. But even more interesting is how each village chooses what to teach. The curriculum varies so much from one town to another that it blew my mind. How many things we can teach, learn from each other, that is why we do this work….”