In its political-economic diagnosis, CNI recognizes dispossession and the war as elements that shape current capitalism. Capitalism in its expansive phase is occupying territories and expelling or integrating in a subordinate way the different forms of social life. Installation of open-pit mines, airports, hydroelectric plants or dams ignores the effects on nature and peoples’ ways of life. In Mexico, the territories of native and afro-descendant peoples are granted to companies or are controlled by criminals. It is a war marked by the capital/life contradiction. In this war, women have raised their voices and are part of the community and territorial defense undertaken by the people.

But the war against indigenous peoples and women is not new. The 21 years that CNI has been fighting are the result of 525 years of the struggle by cultures that have resisted to disappear and that have and are organizing themselves to avoid being annihilated. The women of Zapatista grassroots support and the communities of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) made explicit the conditions of domination and exploitation of indigenous women over 500 years under a colonial regime (EZLN, 2015). Since 1994, many things have changed as a result of the educational processes carried out within the Zapatista communities.

This is how Comandanta Rosalinda explained it (EZLN, 2015):

From the clandestinity, the day came when the women were recruited, and those recruited were recruiting other women, village by village […]. Little by little we lost our fear and shyness, because we now understand that we have the right to participate in all areas of labor and struggle. The revolution has to be made between men and women.

Comandanta Ramona became the first Zapatista to leave the military cordon, located in Chiapas, on her way to Mexico City in October 1996. In her capacity of delegate of the EZLN, she participated in the first CNI of October 12, 1996. The echo of her most emblematic words at that assembly is still felt in the struggles emerging from that network: “Never again a Mexico without us.”The message is clear; it is a cry of resistance and an offensive.

In the face of strategies of territorial dispossession, exploitation and extermination, the CNI has established itself as a plural and flexible network of networks composed of organizations, networks of organizations and networks of communities. CNI members affirm: “We are an assembly when we are together and a network when we are apart.”

In the assembly sessions, reflections are made and decisions happen by consensus. As a network, they deploy mutual support mechanisms to strengthen, foster and endorse the multiple and particular struggles in the territories at the community, regional and national levels.

Faced with a State that refuses to recognize the indigenous cultures and traditional forms of government, the demands for autonomy and self-determination are made through collective and communitarian management of issues such as education, health, security, justice, communication, the environment, etc. If at the beginning it was the demand for the fulfillment of the San Andres Accords that summoned and politically articulated the native peoples, nowadays the Accords are applied de facto in the organization of life and work.1

In a social space configured under the colonial, patriarchal and capitalist structure of a country like Mexico, being a woman and being indigenous means suffering a triple oppression. Racism, classism and patriarchy are some of the social configurations that the women and men of CNI have denounced through their collective reflections. As expressed by Zapatista comandante Esther (2001): “They make fun of us, the indigenous women, because of the way we dress, the use of our language, our way of praying and healing, because of our color, for we are the color of the soil we work.” Such reflections have been accompanied by initiatives to confront relations of domination, even within their own community processes. The Revolutionary Women’s Law is one such initiative resulting in the political inclusion of indigenous women.2

The CNI is a network of networks that articulates communities with women’s representation and national and regional women’s solidarity networks. Women can be spokeswomen, delegates, commissioners, defenders of territory and participants in decision-making spaces. Gender is one of the transversal themes of its political agenda. Women’s organizations and solidarity networks emphasize sexual and reproductive rights, education and women’s political and economic participation. Among the most important are the National Coordination of Indigenous Women (CNMI) and the Women’s Assembly of the National Plural Indigenous Association for Autonomy (ANIPA). The CNMI is a national network of women and was formed in 1997. It is one of the national networks that has established spaces for the political formation of indigenous women. It is an integral education and it is anchored in the communities’ perspective.

The defense of the territory and the struggle for life

Capitalist territorialization promotes the commodification of natural goods and the denial of dignified life through projects of death. In opposition to these projects, the CNI has articulated a language of valuation other than capitalist rationality (Martinez Alier, 2004). Among the original peoples, it is common to find integral ways of understanding life. Equality of women and men is as important as strengthening their normative systems, promoting agro-ecology and recognizing medicinal and spiritual knowledge, etc. The relationship with what they call Mother Earth shapes social relations.

In this assessment of the communities, women are direct participants in the processes of resistance. In Chiapa de Corzo, the Zoque Women’s Movement for the Defense and Dignity of the Land demanded the closure of an open dump that had been polluting the region’s environment for years. The women of Tepoztlan, Istmo de Tehuantepec, Xochicuautla, to name a few places, have defended the forests, water and land, as well as the local flora and fauna. The territory is protected as a space for the community and the reproduction of life. Demands for free and informed consultation are spreading throughout the country and, with them, a great movement of resistance and autonomy.

Women who have led this struggle for life in critical moments have faced the violence of capitalism. The suicidal project of an international airport for Mexico City located in an agricultural zone triggered in 2006 the resistance of women and men in the Texcoco region. The response was the repression of the opposing population in San Salvador Atenco, and in particular the sexual torture of the detained women. The case reached the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and brought to light that the Mexican State denies and covers up violence against women.

It is worth noting that the murders of women are frequent in militarized spaces or where organized crime operates with the complicit approval of some state authorities (Segato, 2016). The Mazateco people of Oaxaca have denounced an increase in femicides at the same time that they seek to dispossess them of their territory.3

Beyond the indigenous peoples

The indigenous women of CNI have spoken of a triple oppression situation. It is the condition of being a woman, indigenous and poor. Maria de Jesus Patricio Martinez presents herself as a symbol of this triple oppression, but also as a spokeswoman for the models of collective resistance. With the whole hegemonic system against her, the possibility of inserting herself in what they call “the politics from above” emerges from a collective endorsement. It is, therefore, a process of direct democracy that can undermine the classist, patriarchal and racist foundations. The strategy of insertion into systemic mechanisms, such as elections, is intended to make visible the threats to models of community life.

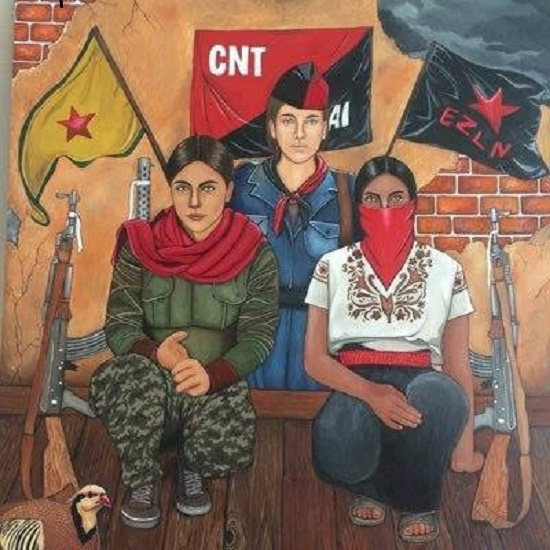

Photo by: Amiel Aketzali Moreno Reyes

The intersectionality of the initiative allows the inclusion of diverse sectors in the call. Outside the electoral institution, the spokeswoman affirmed that this initiative is a call to organize against the capitalist, patriarchal, racist and classist system. To date, numerous territorial and sectorial support networks have been formed in the countryside and in the city. Students, peasants, trade unionists, academics, etc., are united around the anti-capitalist offensive. In the short term, it is planned to take advantage of the situation to make visible the war of extermination against the peoples and women. In the medium and long term, to generate epicenters of autonomy and organizing in the rural and urban areas.

The affinity of the Kurdistan women’s movement Komalen Jinen Kurdistan (KJK) for CIG and particularly for its spokesperson is indicative of the globality of the initiative, which transcends a local or national agenda. Anti-capitalist, feminist, democratic and ecological ideas are part of the common sense of good practices of various groups around the world. For KJK (2017), the CNI is a source of inspiration because of “its experiences of self-government, good governance and communalism; comrade Marichuy is not only the voice of the indigenous people of Mexico, she is at the same time the voice of all the women of the world.”

Bibliography:

Comandante Esther, 2001. Mensaje del EZLN en el Palacio Legislativo de San Lázaro. Disponible en: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2001/03/29/per-indigena.html

Escobar, A., 2016. “Desde abajo, por la izquierda y con la Tierra”. Contrapuntos (blog). Disponible en: https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/01/17/contrapuntos/1453037037_145303.html

EZLN, 2015. El pensamiento crítico frente a la hidra capitalista, vol. I. México, EZLN.

González Casanova, P., 2003. “Colonialismo interno (una redefinición)”. Conceptos y Fenómenos Fundamentales de Nuestro Tiempo, octubre. Disponible en: http://conceptos.sociales.unam.mx/conceptos_final/412trabajo.pdf, consultado el 26-10-2017

KJK, 2017. Carta a María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, vocera del Concejo Indígena de Gobierno, 7 de junio. Disponible en: https://www.centrodemedioslibres.org/2017/06/19/carta-del-movimiento-de-mujeres-de-kurdistan-a-maria-de-jesus-patricio-martinez-vocera-del-consejo-indigena-de-gobierno-cig-cni/

Martínez Alier, J., 2004. El ecologismo de los pobres. Conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración. Barcelona, Icaria.

Segato, R., 2016. La guerra contra las mujeres. Madrid, Traficantes de Sueños.

Original Text: “Nunca mas un Mexico sin nosotras”. La participacion de las mujeres en el proyecto politico de Congreso Nacional Indigena.

Ecologia Politica, No. 54, Ecofeminismos y ecologias politicas feministas (Diciembre 2017), pp. 93-98 https://www.ecologiapolitica.info/nunca-mas-un-mexico-sin-nosotras-la-participacion-de-las-mujeres-en-el-proyecto-politico-del-congreso-nacional-indigena/

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.

Footnotes

- Los Acuerdos de San Andrés se firmaron en 1996 y fueron producto del diálogo entre el Gobierno Federal y el EZLN. Para más información, véase: komanilel.org/BIBLIOTECA_VIRTUAL/Los_acuerdos_de_San_Andres.pdf

- It was enacted in 1993. For more information, see: http//enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/1993/12/31/ ley-revolucionaria-de-mujeres/.

- “Que retiemble en sus centros la Tierra”. Disponible en: http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2016/10/14/que-retiemble-en-sus-centros-la-tierra/, consultado el 25 de octubre de 2017.