Raul Romero*

When in 2001 the Mexican political class denied the possibility of a profound reform of the Mexican State, which through the recognition of the Accords of San Andrés Sakamch’en de los Pobres would open the door to a new relationship between originary peoples and the State, it contributed to the aggravation of various problems and generated consequences that we observe to this day.

One of these has to do with the intensification of the process of accumulation by dispossession, which has accelerated since the reform of Article 27 of the Constitution, which meant the privatization of ejido and communal land. The territorial reordering that Mexico needed for the neoliberal integration with North America was extinguishing the few and diminished lights of the agrarian revolution of the beginning of the century. Recognizing native peoples as entities of public law and harnessing the discussion on territorial self-determination was something that was completely at odds with the neoliberal project. The politicians who rejected the San Andres Accords at the same time reaffirmed their adherence to the neoliberal consensus.

The history that followed is widely known: through projects such as the Plan Puebla- Panama, which would become the Mesoamerica Project and which today has resumed as the misnamed Mayan Train and the Inter-Oceanic Corridor promoted special economic zones and development poles where the peoples had won historic battles in defense of their territory. If North American neoliberal integration had been contained, it was thanks in part to the resistance and strong social and community fabric of the originary peoples, campesinos and broad popular sectors.

Another outcome to be analyzed is the route taken by the peoples who decided to promote their de facto autonomy and continue in defense of their territories. The EZLN communities are the most emblematic case worldwide. In their own words, they say that they went from the time to ask for and the time to demand, to the time to practice their rights. With their resistance and rebellion they have managed to build a very different world based on ruling by obeying, with self-management and self-determination in 43 autonomous entities, among which the 12 Zapatista Caracoles stand out.

The Zapatista communities were not the only ones to opt for this path. Other peoples, communities, neighborhoods, tribes and nations, most of them organized in the National Indigenous Congress, decided to continue defending their territories. Whether rebuilding their communal guards or community police, promoting their community radio stations, strengthening their traditional authorities, strengthening their clinics or autonomous schools or recovering and creating productive projects, these originary peoples have given all their energies in defense of the commons. To confront municipal, state or federal governments, which are linked to powerful national and transnational corporations, indigenous peoples have explored various legal and political avenues of resistance. In some cases, they have been met with attacks by paramilitary groups or armed gangs of organized crime who, through assassinations, disappearances, forced displacements, threats and other violence, have tried to eliminate the peoples in resistance.

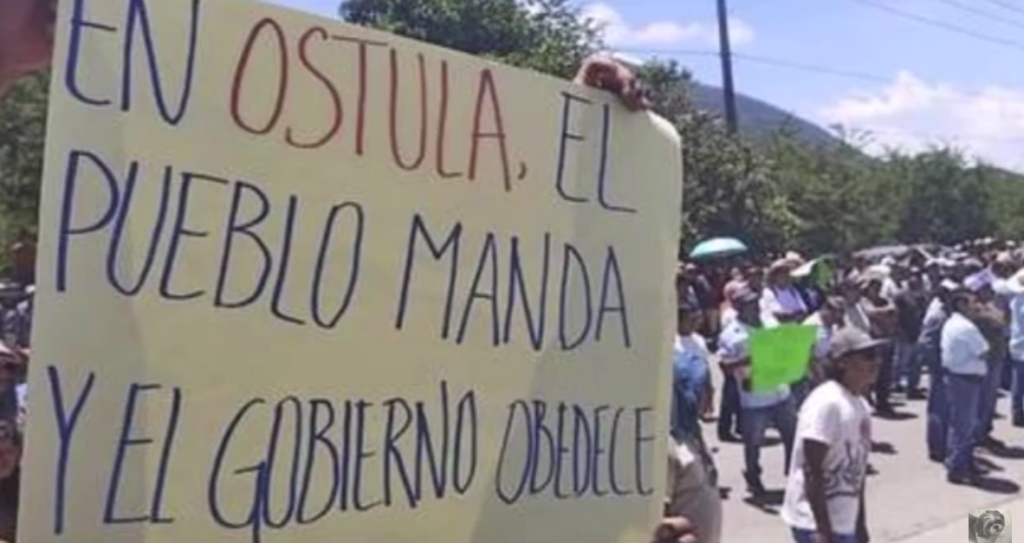

The Nahua community of Santa María Ostula is an example of this violence that the State and capital launch against the people for the purpose of dispossession. In 2009, thousands of community members of Ostula took on the task of recovering hundreds of hectares of land held by caciques and small landowners and desired by tourism, mining, organized crime and precious wood companies.

The people of Santa María Ostula created there an initiative of autonomy that gained the attention of other peoples of the region and the world. To eliminate and displace this Nahua people in resistance, the State and legal and criminal corporations intensified a war that today has left 36 community members murdered and another five disappeared. This violence is not a thing of the past. Last August 10, Froylan de la Cruz Ríos, a member of the community, was disappeared and later found brutally murdered. This happened at the same time that the governor of Michoacán, Alfredo Ramírez Bedolla, threatened to evict the people in resistance.

Within the same strategy of violence of accumulation by dispossession, we could identify the one undertaken against the peoples of the Indigenous and Popular Council of Guerrero-Emiliano Zapata in Guerrero, the aggressions in Oaxaca against the peoples of the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus, the attacks against the Zapatista communities in Chiapas or the assassination in Morelos of Samir Flores Soberanes.

These peoples, who since 2001 have undertaken new strategies for the defense of their territories and life, in fact dispute the legal and criminal corporations in the most concrete terms. A different State would bet on reinforcing them, not abandoning them, denigrating them and waging war against them. This has not happened so far.

* Sociologist

Original text in La Jornada on August 26th, 2023. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/08/26/opinion/017a2pol

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.