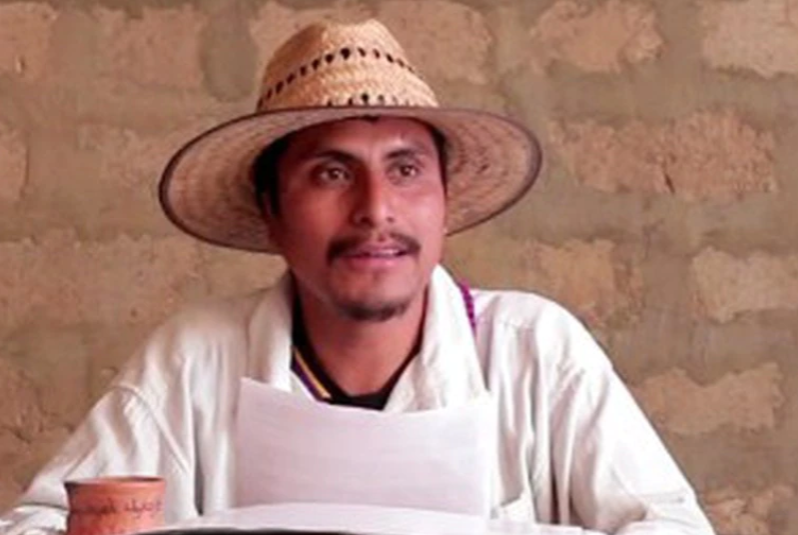

Simón Pedro Perez Lopez / Tsotsil

Tomás Rojo / Yaquí

By R. Aida Hernández Castillo

In the last two months, Mexico’s indigenous movement has lost two of its most lucid and committed defenders of territory and of people’s rights, the Yaqui leader Tomás Rojo and the Tsotsil activist, Simón Pedro Pérez López. Their deaths have been part of a continuum of violence exerted upon their territories, that have included forced displacement, disappearances, femicide, and the use of clandestine graves as part of a “pedagogy of terror” practiced by armed actors who are members of organized crime, of paramilitary groups, with the direct or indirect participation of security forces.

The way in which narco-violence has affected indigenous peoples has been little documented by the social sciences, and silenced by the official reports about the impacts of extreme violence in the country. The risks involved in field research on these issues and culturalist perspectives on indigenous peoples have prevented in-depth analyses about the way community fabrics have been affected by these many violences.

In other texts I have referred to these silences, such as the “multiple absences” of disappeared or murdered indigenous people.

Both the execution of Simón Pedro, member of the Association of Las Abejas de Acteal, and of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) on this past 5th of July, and the forced disappearance and murder of Tomás Rojo one month before were preceded by decades of repression and paramilitarization in their communities, for which the Mexican state has direct responsibility. In the case of the Tsotsil leader, the massacre of Acteal which occurred the 22nd of December 1997 was an antecedent that evidenced the state’s responsibility in the formation of paramilitary groups in the region. At that time we confronted versions that tried to present the murder of 32 women and 13 men as “a product of intercommunity feuds” by reconstructing the political history of the region and showing the state’s responsibility in the formation of indigenous political chiefdoms and in the training of paramilitary groups. (http://www.rosalvaaidahernandez.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1998-LIBROS-La-Otra-Palabra-PDF.pdf). In this context, we denounce the existence of the militaristic transnational culture of death, that crosses borders along with high-powered weapons, torture strategies and techniques of bodily mutilation.

Over this already complex framework, global narco-trafficking networks have been set up. The previous training that paramilitary youth have received has been of great use to the drug cartels now embedded in local power structures. The existence of the Chamula cartel cannot be understood without the earlier formation of the “Institutional Revolutionary Community,” broadly analyzed by Jan Rus, who has documented the history of indigenous chiefdoms that have made use of the extreme violence to expel, murder and rape those who oppose their power.

In the same way, the murder of Tomás Rojo and earlier murder of his comrade Luis Urbano, have been preceded by multiple violences against the Yaqui people opposing the plunder of the aquifer with the construction of the Independence aqueduct. The disappearance of Yaquí youth, forcibly recruited by organized crime, who oftentimes end up in clandestine graves, has also played a part in the territorial control strategies used by armed actors with direct or indirect support from security forces.

Throughout the country far and wide, organized crime linked to the global weapons industry has embedded itself in indigenous communities, physically or culturally kidnapping a generation of young people, whose bodies many times end up becoming markers of territorial control for the cartels. Faced with this politics of death, the indigenous resistances have mobilized to defend the territory and denounce genocide on a national and international scale. The “Journey for Life,” initiated by members of the EZLN and the CNI in Europe proposes confronting the militaristic culture of death with the linking of struggles for life. (https://www.caminoalandar.org/post/viaje-zapatista-por-la-vida-al-encuentro-de-los-pueblos-en-lucha) The strategies of dispossession and death are global, so the resistances must be global.

* Doctor of anthropology, researcher at CIESAS.

This article was published in La Jornada on July 18th, 2021. https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2021/07/18/politica/pueblos-indigenas-narcoviolencia-y-paramilitarismo/

Re-published with English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas.