Seesequasis, a Cree writer from the Canadian prairies, recalled a few months ago that his mother had inspired him to look at photographs of his town’s traditional festivals differently. Where “the public only saw indigenous people in the context of traumas and tragedies” they had to look for their positive content, “because without the strength and resilience of families, our culture and our languages would not have survived.”

Referring to an iconographic display about his own First Nation, Seesequasis made valid points for many indigenous peoples of the continent: “They are snapshots of a moment in time, like all photographs, but they also frame the indigenous experience in a totally positive way by showing humor, dignity, joy, living off the land” (Radio Canada, May 2, 2023).

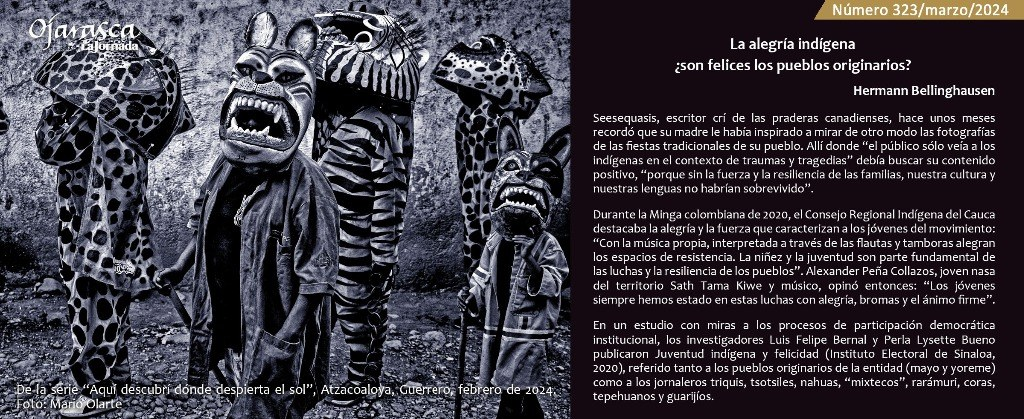

During the Colombian Minga of 2020, the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca highlighted the joy and strength that characterize the youth of the movement: “With their own music, performed through flutes and drums, they brighten the spaces of resistance. Children and youth are a fundamental part of the struggles and resilience of people.” Alexander Peña Collazos, a young Nasa from the Sath Tama Kiwe territory and musician, said then: “We young people have always been in these struggles with joy, jokes and a firm spirit.”

In a study aimed at the processes of institutional democratic participation, researchers Luis Felipe Bernal and Perla Lysette Bueno published Indigenous Youth and Happiness (Instituto Electoral de Sinaloa, 2020), referring to both the native peoples of the entity (Mayo-Yoreme) as well as the Triqui, Tsotsiles, Nahuas, “Mixtecos”, Rarámuri, Coras, Tepehuanos and Guarijíos day laborers. To complete their study, they review the concept of “happiness” in thinkers such as Amartya Sen, Ruut Veenhoven, Martin Seligman and others.

You see that today comparative studies and surveys on happiness indices in towns, regions and nations are in vogue among economists and demographers, and there are several lists of the “happiest” according to various criteria. How to consider such a subjective and changing issue according to culture and one’s own experiences? In its core part, the cited work (https://biblioteca.ieesinaloa.mx/files/productos/1648702589_P_JUVENTUD-INDIGENA-Y-FELICIDAD.pdf) identifies three groups: semi-nomadic migrants, established migrants and local peoples who may or may not live and work their own lands or be salaried.

Of the first group, Jesús Álvarez Hernández, a young man originally from Oaxaca, points out: “What makes us happy is finding work and being able to find other places to work in the fields… I am happy because we have work and we can save a little to take home to Oaxaca.” This illustrates the mentality of the worker who migrates in search of work and longs to send remittances.

Of the second group, Juan López, Triqui leader in Villa Juárez Navolato, comments: “Being with my family, seeing that my children have what I couldn’t have, that they can go to school, that my family and I can share, Having a job and supporting my colleagues who come from other parts of the country in every way I can is something that makes us happy… That my children and those of my colleagues have those opportunities is good.”

For Bernal and Bueno, “it seems that, as the theory of happiness points out, these migrant ethnic groups that have settled in the entity have found part of their happiness in their own search for their subjective well-being.”

The indigenous people of Sinaloa denote other references. Thus, a group of young people from La Playita de Casillas admit that being dancers and revelers “is what really makes us happy… all year round we meet to practice our dances, stay in shape for when the holidays come or if someone invites us to an event, or traditional party as in a response or command. We dance so that our holy protector is happy with us, as we are with him. Being invited by other communities to their parties, and having competitions to see who has the most stamina, that is something we love; being revelers is something that makes us be part of what we are, indigenous people, and we love it.”

For Selene López, a Yoreme living in Culiacán, the traditional festivities make her return to her homeland: “My children have lived far from the community where we are from since they were very young , they understand little, but they like to go to the festivals. I see them silently observing the dancers and everything that happens there, with a certain enthusiasm. There is something inside them that is still Yoreme.” The work quotes Iris Villalpando: “When there is no one who speaks the language, when there are no more prayers, when there is no one who celebrates and loves the deity of the mountain, when there is no one who all this makes happy, then our culture will have died, there will be no more one of us, there will be no Yoremes on Earth.”

Beyond the obvious, a multitude of “misfortunes” threaten this happiness: inequality, poverty, discrimination, violence, uprooting. We cannot overvalue or idealize the “Wretched of the Earth” who populate the incessant specific complaints, economic indicators, speeches and propaganda of governments, parties and humanitarian agencies.

The poor, sad, persecuted, repressed, dispossessed Indian is better suited to the “white” and Westernized mentality, whether capitalist, populist or revolutionary. In more ways than one, they are the screwed, the humiliated and the offended on the map of reality in Abya Yala. That “quiet pain” of the indigenous narrative is not just an invention. It constitutes evidence from the European colonization that began five centuries ago. Whatever happened before 1500 goes beyond the intentions of these lines.

Good Living has become much more than a slogan. It is an existential and political program that fuels struggles. The Colombian Minga, Mexican Zapatismo, the North American Pow Wow, carnivals, patron saint festivals and ancestral celebrations reformulated by Spanish Christianization show how changing and constant the festivals are. But Good Living essentially participates in the collective and community life of indigenous peoples.

With the direction that environmental deterioration and social relations are taking in a continent devastated by organized crime and the anomy of rampant capitalism, it now turns out that perhaps the key to the happiness and survival of humanity lies in these disdained peoples, with everything and the militarization of a thousand heads that screws them in Araucanía, Amazonia, Lancandonia, Tarahumara or Cauca.

A study published in the journal PNAS, “High life satisfaction reported among small-scale societies with low incomes”, led by researcher Eric Galbraith, “measured the life satisfaction” of those who live “on the margins of the globalized world”, members of indigenous populations with limited economic resources. Despite the “poverty” of the Mapuche of Lonquimay, in southern Chile, the reported level of satisfaction is 8.1 out of 10. In Amambay, Paraguay, the Guaraní reach 8.2; the Collas of the northern highlands of Argentina at 8 and the Ribeirinhos of the Brazilian Amazon, 8.4. Meanwhile, the European Union had an average of 7.2 in 2021, and the happiest country, Austria, 8 (https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2311703121).

Galbraith found that in societies with better scores in their perception of happiness, there is a strong sense of community, a close bond with nature and a deep spirituality that would explain their well-being beyond money.

Original article by Hermann Bellinghausen at https://ojarasca.jornada.com.mx/2024/03/09/la-alegria-indigena-son-felices-los-pueblos-originarios-323-5091.html

Translated by Schools for Chiapas.