Guatemala in Chiapas at Sendas

Although the full extent of the barbarism of the armed conflict in Guatemala will never be known, the investigation that resulted in the 3,500-page report “Guatemala, Memory of Silence” found that the 418 months that the conflict lasted left over 200,000 dead and thousands more disappeared. Over 42 thousand women were victims of rape and some 29 thousand of them were subsequently murdered. 93 percent of the rapes were attributed to the army.

The years 1978-1985 were the bloodiest in the conflict, which began in 1962 and lasted until 1996. Atrocities continued between 1986 and 1996 despite being more selective in their nature. The Mayans were the greatest victims of the conflict with the army committing some 626 massacres against them in what can only be seen as acts of genocide against the indigenous peoples, who represented 60% of the population of 11 million people at that time.

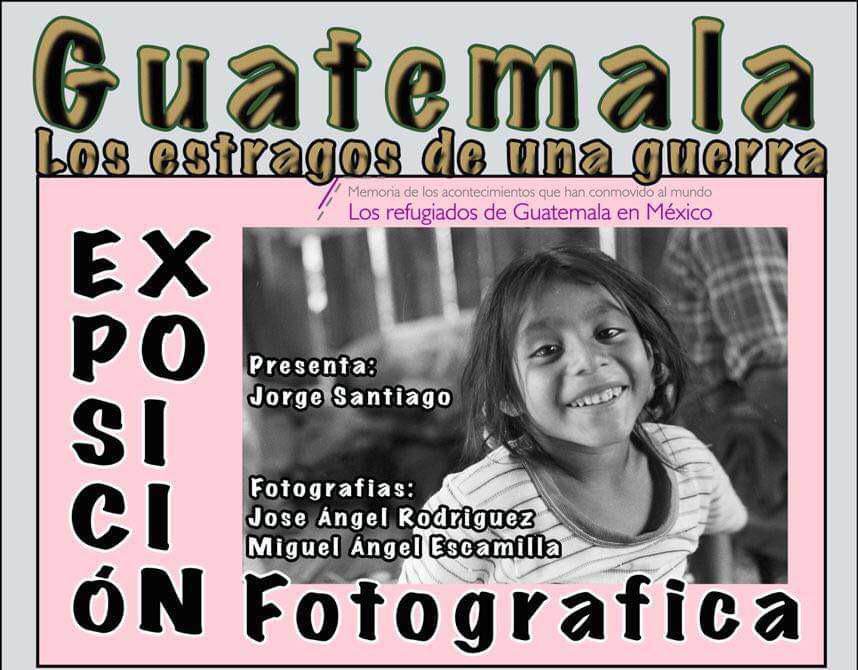

One consequence of the Guatemalan tragedy was the arrival of over 200,000 refugees to Chiapas, where they lived in over 90 camps along the border. Many of these arrived as a result of the counterinsurgency drive from 1980-1982 by the Guatemalan government of Lucas García and Ríos Montt, when they applied a scorched earth policy resulting in numerous massacres, disappearances, kidnappings, torture, burning of whole communities, aerial bombing and persecution of the civilian population. The photographic exhibition “Guatemala, El Tiempo del Refugio en México” currently on display at Sendas in San Cristóbal de Las Casas is a stark reminder of those times and gives us a glimpse of daily life in the camps, with images from José Ángel Rodríguez and Miguel Ángel Escamilla Carmona. It is based on an idea of Jorge Santiago and curated by Anny Zuñiga.

Although arrival in Mexico provided some level of respite for those who fled the conflict, the refugees lived in constant fear of incursions by the Guatemalan Army and were largely unprotected by Mexican forces who did not want to become embroiled in the conflict. Conditions were dreadful, largely due to corrupt mismanagement of distribution of UN food supplies by government agencies. Of three camps surveyed in early 1984, it was found that the refugees had received 1 kg. of dried fish, 2 kg. of dried beans, 1 kg. of powdered milk, and 12 kg. of corn meal each in the previous three months, a quantity of food that is not even sufficient for one person for two weeks.

Refugees were forced to stay in the area by the Mexican government to appease the US. Although they were recognized as refugees in Mexico, this was not the case with its northern neighbor, where detected arrivals were deported. Although the Mexican authorities would probably have been happy to do the same, they did not do so to avoid international outrage, choosing instead to implement policies and practices that largely ignored but attempted to contain the problem. Notwithstanding, at the start of the conflict Mexico deported between two and three thousand people at the petition of the Guatemalan government and all were killed on crossing the border. Some were sent to destinations as far away as South Africa or Canada.

Among other measures, these attempts at contention involved forbidding the refugees from growing their own food when they could have been self-sufficient. Instead, they were permitted to work for extremely low wages, driving down local rates and thereby causing conflict with local workers in some cases, whose circumstances in Chiapas meant that they were already under great economic strain. Fortunately, sympathy and solidarity generally surpassed resentment and rejection.

The determination of the refugees to overcome the many obstacles placed before them resulted in them organizing their own independent structures to address problems of health, education, administration and led to them achieving some level of autonomy that was to have an impact on the newly founded and growing Zapatista movement in the area.

One example of this was the education system of the Guatemalan refugees. In an effort to resist their children losing their Guatemalan Mayan identity through schooling offered by the Mexican government, the refugees chose members of their community to teach the youth about their culture and history in their own languages. This was to have a profound effect on the Zapatista autonomous schools which Schools for Chiapas has supported over the years. Their self-organization also set an example of Mayan peoples of different linguistic backgrounds working collectively to solve common problems, now common practice in the Zapatista Juntas de Buen Gobierno.

The refugees began to fight for the right to return to their country in 1987, choosing representatives to negotiate conditions with the government for a safe, collective and organized passage. These negotiations would last for five years until 1992 when the first agreements were signed, resulting in the first mass return in 1993. The conflict would drag on for another three years before the signing of a definitive peace agreement in 1996.

Memory

In Guatemala there is a place named

Victory of the 20th of January

In memory of the day the refugees crossed the border for the first time since they were expelled in 1982

You will blossom, Guatemala

You maintain the millenarian resistance,

like the mountains,

like the rivers,

like the peoples.

Men, women, boys and girls,

sown in the furrow to germinate.

They are invincible presences.

Wind, word, dance, scream, faces.

Enveloped in incense and dressed for combat

they will light the candles.

What gives consistency to this dignity?

(Jorge Santiago)