The EZLN went from an armed insurrection that suddenly introduced the reality of indigenous peoples to the national agenda, to a political movement that advances through autonomous communities

The Zapatistas burst onto the political scene in Mexico in the early hours of January 1st, 1994, when thousands of indigenous combatants took up arms and took five municipal centers in Chiapas, in the extreme south of the country. From San Cristóbal de las Casas, the rebels presented themselves to the world with a declaration of war on the Mexican Government and defined their origin in the historical processes that, since the Conquest, were decisive for the uprising. “We are the product of 500 years of struggles,” explains the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, which called to join the insurgency and claim the rights that have been historically denied: “work, land, shelter, food, health, education , independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace.”

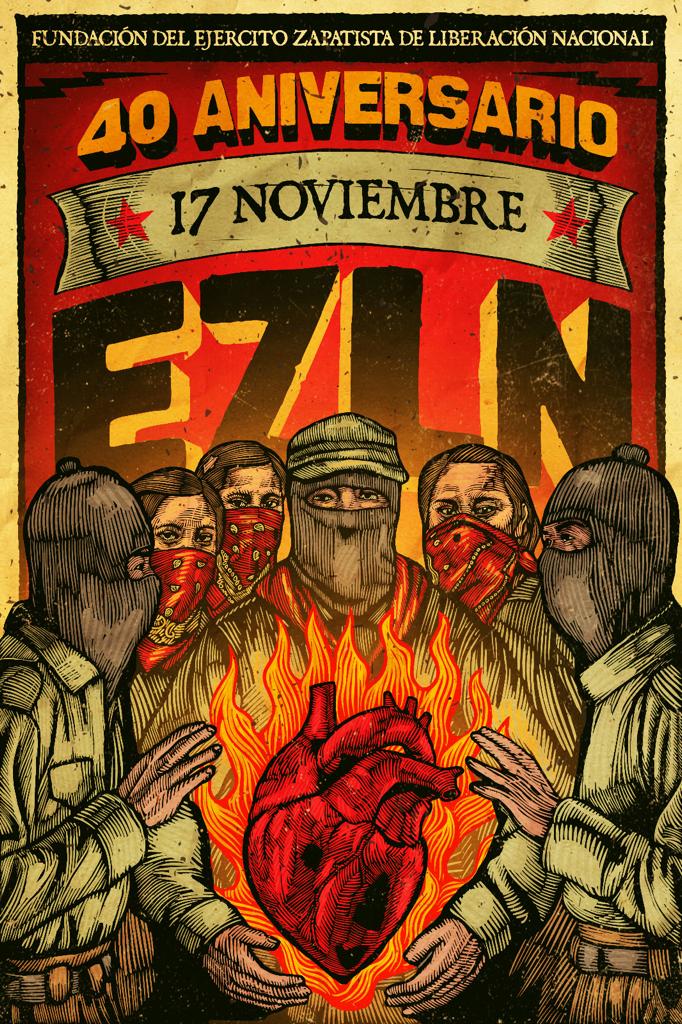

The rebellion, however, began to take shape a decade earlier: in November 1983, a group of six members of the extinct National Liberation Forces (FLN)*1 a guerrilla founded in 1969 in Monterrey and disappeared during the Dirty War in Mexico*, built the first camp of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in the Lacandon Jungle. Ten years later, after quietly building forces, linking up with politicized indigenous communities that formed a social base that numbered in the tens of thousands, and learning military tactics, the EZLN suddenly introduced the reality of indigenous peoples into national history.

The armed uprising contrasted with the narrative that the Government of Carlos Salinas de Gortari intended to bequeath for the 21st century: 1994, an electoral year and the closing of his six-year term of office, marked the entry into force of the Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada (NAFTA), an agreement that, on paper, strengthened economic development as the engine for the modernization of the country. After the first intelligence reports, which dismissed the indigenous origin of the uprising and attributed it to foreign cadres with experience in Central American guerrillas, the Government’s initial response consisted of launching a military offensive to quell the rebellion.

With a deployment of just over 12,000 soldiers, the Mexican Army recovered most of the positions in rebel hands during the first four days of combat, forcing them to retreat. However, the image of the Zapatistas, with their faces covered by balaclavas and red bandanas tied around their necks, went around the world, gaining sympathy, especially among indigenous peoples, university students and left-wing intellectuals. Their demands stirred the hope of an alternative world, just when the struggle between socialism and capitalism seemed definitively resolved.

The Start of Negotiations

After a series of indiscriminate aerial bombardments and the beginning of an investigation led by the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) into summary executions committed by federal troops, the clamor for a ceasefire culminated in a massive protest in the Zócalo of the country’s capital held on January 12th, 1994, where thousands demanded that the Government withdraw the Army from Chiapas, a condition of the Zapatistas to establish dialogue. The same day, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari announced the ceasefire and the bases were established for dialogue for the first time since the uprising: while the Government appointed Foreign Minister Manuel Camacho Solís as commissioner for peace, the Zapatistas proposed Samuel Ruiz, bishop of San Cristóbal de las Casas, as a mediator in the process of pacification.

The dialogue between the Peace Commission and the EZLN officially began on February 21st, with headquarters in the San Cristóbal cathedral. For just over a month, the general tone of the meetings stagnated between the demands presented by the Zapatistas and the unsatisfactory responses of the Government, contained in a first draft brought to consultation between the Zapatistas and their support bases. The rejection led to a first suspension of negotiations, a scenario that was constantly repeated during the rest of the year.

In parallel, and despite the fact that the incoming president, Ernesto Zedillo, offered a peaceful solution to the conflict and assured that there would be no violence on the part of the Government, the Army maintains a siege around the Zapatista areas of influence in Chiapas, with constant interference and attacks. The harassment, denounced by the rebels as a “low intensity war” and denied by the armed forces, became a constant in the conflict, giving rise to the appearance of paramilitary groups and a wave of violence that caused the forced displacement of thousands of indigenous people.

The Foundation of Autonomous Municipalities

At the end of 1994, the EZLN announced the foundation of thirty autonomous municipalities in its area of influence, the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ). The Government’s reaction was to intensify the military presence in Chiapas and for the first time since the beginning of the conflict, it issued arrest warrants for terrorism against those who they claimed were leading the insurrection in Chiapas. Among them, Subcommander Marcos, the main spokesperson and the most visible face of the Zapatistas since the uprising, whose identity is revealed: according to State intelligence reports, he is Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, a man from Tamaulipas and former university professor.

The Government announcement was followed by another popular mobilization in the heart of the capital. On March 11th, 1995, under the slogan “We are all Marcos,” tens of thousands gathered in the Zócalo to demand an end to militarization and the dropping of charges against the Zapatistas. At the same time, the Law for Dialogue, Conciliation and Dignified Peace, an initiative that sought to create the legal framework to solve the conflict, advanced in Congress and was sent to the rebels.

The San Andrés Accords and The Zapatista Caravan

Between October 1995 and February 1996, the EZLN and the federal government held the first negotiations that resulted in the San Andrés Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture; a document that, on paper, laid the foundations for establishing a new relationship between the Mexican State and the indigenous peoples based on their full constitutional recognition, as well as their political and cultural rights, in addition to their autonomy. However, the commitment to modify the Constitution foundered as a bill due to the proposed modifications to the agreement, both by the Government of Ernesto Zedillo in 1997, and that of Vicente Fox in 2001.

The failure to achieve the San Andrés Accords, which became a dead letter, marked a watershed in the fragile relationship between the Government and the Zapatistas. On December 1st, 2000, Vicente Fox took office as the new president of Mexico, consolidating political alternation after seven decades of PRI governments. In his inaugural speech, Fox especially addressed the indigenous peoples and committed to solving the conflict, promoting the essence of the San Andrés Accords as a bill, and building peace: “In Chiapas, it will be actions, not hollow words, the backbone of a new federal and presidential policy that leads to peace,” the president said.

One day after his inauguration, the EZLN announced a caravan made up of 24 representatives that would travel through 17 states of the country until reaching Mexico City, in order to demand that the government comply with the San Andrés Accords. In March 2001, the Zapatistas reached the heart of Mexico City. Supported by tens of thousands, in addition to compliance with the Accords, they demanded the demilitarization of Chiapas and the release of political prisoners to re-engage in dialogue: “Mexico, we do not come to tell you what to do, we come to humbly ask you to help us. Don’t let another day pass until the flag has a place for all of us,” Marcos said.

The Creation of the Caracoles and The Other Campaign

In August 2003, the EZLN announced the largest social reorganization in the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities with the creation of the Caracoles, five regions that from then on group together the more than 30 MAREZ. With the Good Government Councils, institutions of indigenous self-government established in each Caracol, the Zapatistas put into practice a process of autonomy that marks the definitive withdrawal of the military activities of the EZLN, a characteristic that they retain to this day.

With the 2006 presidential elections approaching, the Zapatistas launched the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle in June 2005, a position in which they called for establishing a “program of national struggle” and a new Constitution. The campaign, supported by indigenous peoples and an increasingly broad social base, led Subcommander Marcos and other members of the General Command to tour the country and meet with left-wing political and social organizations. Zapatismo not only once again put the abandonment and discrimination of indigenous people at the center of the debate, it also emerged as a critical alternative to political parties and the electoral system in general.

María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, First Indigenous Candidate

On the eve of a new electoral year, in May 2017 the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), a body created in October 1996 within the framework of the San Andrés Accords after a call from the EZLN to the indigenous peoples of Mexico, decided to present itself for the presidential elections with a unitary candidacy, supported by the Zapatistas: María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, Marichuy, a woman defender of human rights and traditional Nahua doctor, was appointed as spokesperson and representative of the Indigenous Government Council for the elections of 2018.

In October 2017, Marichuy registered with the National Electoral Institute (INE) as an independent pre-candidate for the 2018 presidential race and began a tour of the country that she interrupted after a road accident. Although the candidate did not manage to comply with the signatures required to register with the authorities as a presidential candidate and faced endless obstacles such as the refusal of banks to open an account, as well as the constant failures in the INE mobile application to collect signatures, the Zapatistas once again put discrimination and indigenous rights at the center of the debate during electoral times.

In November 2023 and after months of warnings about the escalation of violence that Chiapas faces derived from the struggle between criminal groups, the EZLN announced the most recent modification to its civil structure. In a document signed by Subcommander Moisés, the Zapatistas announced the disappearance of the MAREZ and the Good Government Councils. The measure, which does not affect the structure of Zapatista autonomy, transfers the power of the Good Government Councils and the MAREZ to the Local Autonomous Governments (GAL), an action forced by the extreme situation that the State is going through, with “blockades, assaults, kidnappings, protection rackets, forced recruitment and shootings,” the statement explains.

Original article at https://elpais.com/mexico/2023-11-20/ezln-asi-ha-caminado-el-zapatismo-a-40-anos-de-su-fundacion.html

Translated by Schools for Chiapas.