Edited by Yessica Morales

*The article is a product of different forms of relationship, a critical and decolonial ethnography. That is, “it tries to transform the ways of observing, talking, being, feeling and acting in educational processes.”

In the article, “A Tsotsil community building autonomy through education in Zinacantán, Chiapas, Mexico,” researchers, teachers and students* approached the work of autonomy through the educational process within the community of San Isidro La Libertad in Zinacantán. Said process focuses on the accompaniment and experience of education promoters, who have linked the learning and daily knowledge of the community, with their own learning process.

This said, the experience is taken from the centrality of the cultural practices that social movements, in particular those of the indigenous peoples, have taken up as a political project, hand-in-hand with the daily construction of their autonomies. This gives rise to other ways of thinking and acting in the educational processes, and also recognizes the links between social inequality and cultural diversity.

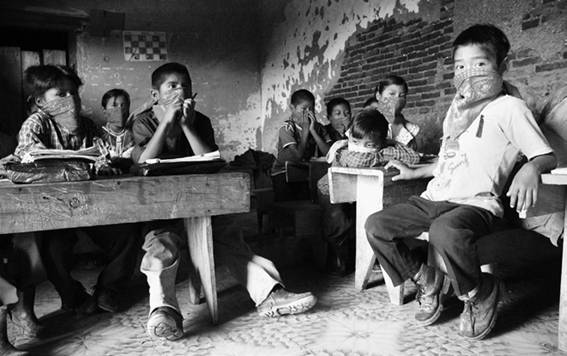

The researchers told the story of the school and how the classroom space shows another kind of movement and relationship – one that has to do with respect, trust and caring among everyone. In particular, they relate the experience of the current promotora, who graduated from the first generation of autonomous primary school and played a leading role in the creation of the secondary school.

Autonomous Education

With regard to the creation of the autonomous school, the investigation points out that it is linked with the processes of autonomy of the indigenous peoples. A community that belonged to Chajtoj, in 1994 joined the struggle of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), which ended up dividing into two groups, one reason being that children were not allowed to enter the school for being Zapatistas.

In 1998, the EZLN reported the formation of the autonomous municipalities, and the autonomous council was named. However when one person joined a political party, this created a new division, which resulted in two moments of tension which raised the question of having support of the political parties or achieving autonomy, but they ended up marking the creation of the community of San Isidro de la Libertad in 2008 as an autonomous territory.

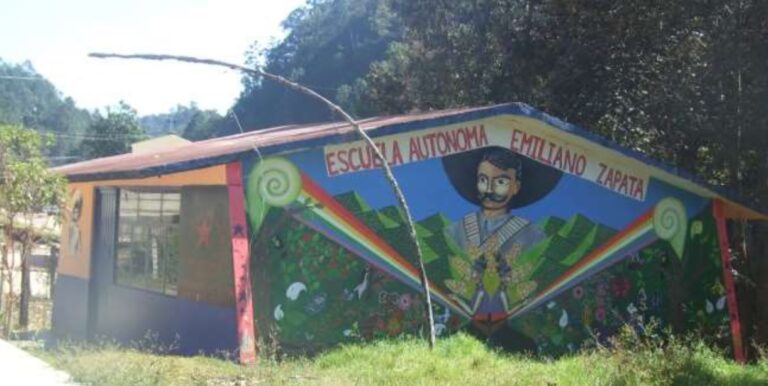

On the other hand, the autonomous families of the community live together in the same territory with those non-autonomous of San Isidro and Chajtoj, as is the case with the educational spaces, with two official schools and one autonomous. The latter went through a process of struggle for its territory and facilities, but the community claimed its right to this area.

And so, during 2012 and 2013, the first promoters were trained with the Inductive Intercultural Method (MII), training processes promoted by diverse educational institutions of Chiapas. MII develops pedagogical work based on the participation of students in the daily social activities of the community, where indigenous knowledge is implicit. These then are coordinated and contrasted with the scholarly scientific knowledge, with culture being a factor that participates and is actualized.

The Emiliano Zapata Autonomous School has a curriculum design which is collectively developed by the assemblies; they linked agricultural and ceremonial activities, and adjusted the school calendar to that of the harvest. In this process, the researchers joined in as assistants, whose support was requested by the authorities.

In combination with the above, with the authorization of the community, they broadened the invitation to students of pedagogy and anthropology, local, national and international volunteers, and along with mothers and fathers, autonomous authorities, and assistant researchers, an intercultural educational community was formed.

The researchers explained that the promoters are supported by members of the Network of Inductive Intercultural Education (REDIIN), who meet periodically to discuss their experiences, what they have learned, and problems that arise.

Maria and the Secondary School

In April 2013, Maria, being one of the students who graduated from the autonomous elementary school, asked her parents to talk to the authorities about joining the activities of an autonomous high school for the technical training of her students. At that point, two mothers, two students from official schools and two from the autonomous elementary school joined in.

“I want to continue studying, because I have already finished and I am worried about not having anywhere to go to train as a teacher. My parents told me to talk to the authorities and ask Malena to help us with more teachers. That’s why we came today to ask them to support us to open the technical high school, because I want to teach in elementary school. I want to be taught techniques,” said María in 2013.

Because of this, the autonomous technical school was created, coordinated by the outside team that arrived and with the support of the residents of San Isidro de la Libertad, who shared their knowledge and techniques for working with the students. The researchers noted that the families and authorities gave their consent and permission in the assembly for their stay.

One fundamental element for the continuation of autonomy was the elaboration of the curriculum, based on historical elements of the formation of this faculty. They also established a space where each student would create their own school materials.

The New Education Promotor

The young promotora, had just been chosen by the community, and would give continuity to the work of the pair of promoters who left the position in 2016. With María, another step was taken to strengthen the school— one of the distinct features of these academic institutions is that their promoters do not receive pay, and their work is compensated by each community according to the available resources and organizational processes.

Contribution for the support of the promoters is a recurrent problem in the processes of autonomy that is solved in different ways, according to the conditions and ways of each community. In the case of young promotores or promotoras, there is no major problem, since their families assume their subsistence.

In María’s case, she is part of the collective of women embroiderers. The community requested support to assist her, and at the beginning they gave her guidance in her daily activities, which allowed them to get to know her work within the collective. In April 2016, they made the formal change of education promoters.

*Researchers, teachers and students:

María Elena Martínez Torres, professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS). Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS).

Kathia Núñez Patiño, teacher and researcher in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Autonomous University of Chiapas (UNACH).

Isabel López López, Master’s student in Social Sciences at the Center for Higher Studies of Mexico and Central America (CESMECA).

Ana Luisa Borrayo Mena, Intern in International Relations at the University of San Carlos of Guatemala (USAC).

This article was published on January 31st in Chiapas Paralelo. https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/01/incentivan-a-la-autonomia-en-comunidad-tsotsil-a-traves-de-la-ensenanza/. English translation by Schools for Chiapas.