By Carlos Fazio

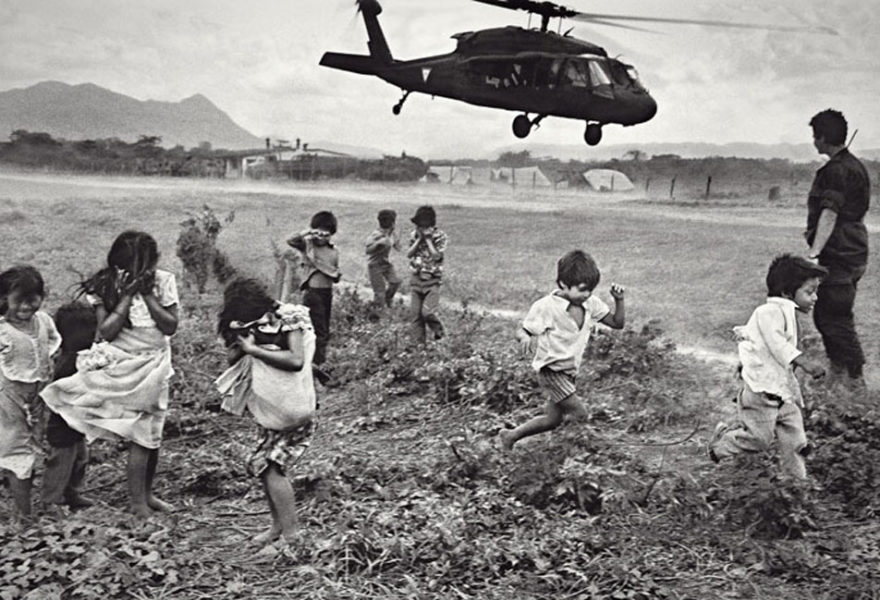

The “humanism” of the Fourth Transformation did not reach the Mexican southeast. Chiapas is a powder keg about to explode. This is not due to the absence of the State: given that it is a territory of great geopolitical and geoeconomic importance – plus it also borders Guatemala. For national security reasons there is a strong military presence , the National Guard and the different police forces. It became even more acute after the imposition, by the governments of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, of militarized control (by the Mexican State) of the migratory waves coming from Central America, which became even more acute.

In Chiapas, a series of contradictions, concepts and categories tangle, intertwine and or oppose one another including, on one hand: internal colonialism; neo-extractivism (the main axis of the capitalist megaprojects of the Transisthmus Corridor and the misnamed Mayan Train); diffuse warfare; necropolitics; racism; state terrorism; population control; and forced displacement. And on the other hand: community; self-determination; autonomy; collective rights; anti-systemic and counter-hegemonic principles; organization; resistance; defense of land and territories; and dignity.

The EZLN took up arms and declared war on the Mexican State on January 1, 1994. After 12 days of confrontations, the government of Carlos Salinas decreed a ceasefire against the Zapatista peoples and negotiations began with the mediation of the then bishop of San Cristobal de las Casas, Samuel Ruiz. After the San Andres Dialogues, Ernesto Zedillo’s regime did not comply with the agreements and the EZLN dedicated itself to the construction of de facto autonomy in its territory in a civil and peaceful manner, while being a key actor in the advancement and exercise of the rights of the original peoples. Nevertheless, it continues to be an armed political-military actor.

Since 1995, the Secretary of National Defense (Sedena) initiated a phase of irregular warfare and paramilitarization of the conflict, which corresponded to the guidelines of the so-called Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan. This plan had as its strategic-operational objective “to destroy the EZLN’s will to fight, isolating it from the civilian population and achieving the support of the latter, for the benefit of the Army’s operations”. The tactical objectives of Plan Chiapas 94 included “to destroy and/or disorganize the political and military structure of the EZLN”. For this purpose, together with intelligence, psychological, population control and logistical operations, it instructed to organize, train, advise and support “self-defense forces or other paramilitary organizations” (sic). And it added: “In case there are no self-defense forces, it is necessary to create them.” It was ordered to “secretly organize certain sectors of the civil population – among others, cattle ranchers, small landowners and individuals characterized with a high sense of patriotism – who will be employed on orders in support of our operations”.

According to the plan, training, advice and support of the self-defense forces and other paramilitary organizations were to be provided by the Army. The paramilitaries were to participate in Sedena’s security and development programs. Among other tasks, they were to provide information to feed the branches of military intelligence (counter-information, combat intelligence, intelligence for the support of psychological operations, internal situation intelligence).

The Acteal massacre in December 1997 -when 45 Tsotsil indigenous people were murdered while praying in the hermitage of that community in the Chenalho municipality by the PRI paramilitary group Red Mask and undercover Army troops-, was a military action that followed the guidelines of the Manual of irregular warfare, counter-guerrilla operations and restoration of order, published by the Sedena. It teaches how to combat the insurgency. Quoting Mao Tse-Tung, it states that “the people are to the guerrilla as water is to the fish.” But to the fish, it adds, “life in the water can be made impossible, stirring it up, introducing elements harmful to its subsistence, or fiercer fish that attack it, persecute it and force it to disappear.” Hence, paramilitaries.

Almost 25 years later, the Regional Organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo (Orcao) plays the role of the Red Mask in the Acteal massacre. And together with Orcao, criminal groups – in complicity, collusion or under the protection of state security agencies – carry out in Chiapas the same terror and chaos-generating tasks that criminal organizations developed in geostrategic zones of Mexico. These are the states located in the Burgos and Sabinas basin (Coahuila, Nuevo Leon), rich in uranium, coal and hydrocarbons, considered “Zeta territory” during the diffuse war of Felipe Calderon or in the “hot land” area of Michoacan, where the Army armed a civilian self-defense group (Hipolito Mora, Juan Jose Farias, Miguel Angel Gutierrez, Jose Manuel Mireles and others) to confront the Knights Templar of Servando Gomez, La Tuta.

In all cases it is a matter of destroying the communitarian social fabric through necropolitics, a category that, according to Achille Mbembe, implies the decision of who can live and who must die at the hands of “war machines” (state and private) to generate massive death, that exhibits the logic of 21st century capitalism as “administration and work of death”, with the material destruction of human bodies and populations deemed disposable and superfluous (matables, says Agamben). The objective of terror and necropower is social subjugation; the subordination of the other as part of a predatory dynamic of dispossession, expropriation and reterritorialization for the purpose of economic domination.

Original text published June 12, 2023 in La Jornada. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/06/12/opinion/015a2pol

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.