By Jeny Pascacio

Two years ago, violence, disappearances, displacements and recruitment of people due to the territorial dispute between two Mexican cartels completely disrupted the lives of different communities in Chiapas.

One of the groups identified as the Sinaloa Cartel has had a presence in this entity since the late 1980s, as Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo,” had a lot of influence, as well as possession of properties.

“Local organized crime groups were linked to this larger group, we must remember that they are networks and function as cells that reproduce themselves,” explains for Avispa Mídia, Carla Zamora Lomelí, researcher of the Socio-environmental Studies and Territorial Management group at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Ecosur).

In 2018, in elections for president, governor and mayors, criminal violence worsened in southern Mexico. “It may seem coincidental, but it is not so much,” says the researcher, as the arrival of Morena coincided with the incursion of the Jalisco Cartel – New Generation (CJNG).

The cartels began to contest the municipalities and the violence was replicated in June 2021 in the elections of 118 mayors and local legislators. In municipalities such as Pantelhó and Frontera Comalapa there were no security guarantees even for the workers of the electoral bodies, a municipal council was appointed and the violence started to become more visible.

On July 5 of the same election year, Simón Pedro Pérez López, human rights defender and member of Las Abejas de Acteal was murdered in front of his son and father in the public market of Simojovel.

In the report “Blessed are those who work for justice…”, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) reports that before the crime, Simón Pedro denounced to the the Secretary of Government the situation of violence in Pantelhó, Simojovel and Chenalhó due to the siege by armed groups linked to organized crime.

Three days later, on July 8 (2021) in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Gilberto Rivera Maravilla, alias “El Junior” or “Jr.,” son of Gilberto Rivera Amarillas, “El Tío Gil,” operator of the Sinaloa Cartel in Chiapas, was murdered.

Since then, the struggle of criminal groups has expanded into other territories. From the southern border it extended to the Sierra; then to the central, northern and highlands of Chiapas, although linked to local criminal groups, such as Los Herrera in Pantelho or “El Caracol” in Chamula, in the highlands, which are linked to or have alliances with groups of greater reach.

Los Herrera are linked to the Sinaloa Cartel, but after the murder of Jr. they were stripped of control of Pantelhó by an armed group calling itself “El Machete,” which presented itself in the media as self-defense, posing with high-powered weapons.

A month later, in August 2021, the Chiapas Indigenous Justice Prosecutor, Gregorio Pérez Gómez, who was investigating violence between Los Herrera and El Machete, was assassinated in San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

Fleeing between bullets

Although violence is widespread, the dispute between the Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación cartels has particularly changed the daily life of towns in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, bordering Guatemala, such as Frontera Comalapa, Chicomuselo, Motozintla, Siltepec, Amatenango de la Frontera, Mazapa de Madero, La Grandeza and El Porvenir.

The presence of cartels in these municipalities is related to the flow of migrating people. For years, this population fallen victim to various crimes ranging from sexual violence, robberies, kidnappings, human trafficking and disappearances.

Between 2018 and 2023, the State Attorney General’s Office registered 201 investigative files for disappearance of people by individuals, of which 165 are in process, 22 without criminal action, 11 without prosecution and accumulated three more.

On the other hand, the National Registry of Disappeared and Missing Persons in the same period reports 810 cases in five municipalities: 144 in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, 41 in San Cristóbal de las Casas, 108 in Tapachula, 104 in Comitán and 55 in Frontera Comalapa.

However, according to the Mothers in Resistance Collective, Melel Xojobal, Mesoamerican Voices and Frayba, there are no real official figures on disappearances, both of people in transit and of residents.

Disappearances began to be reported more strongly after the confrontations in May 2023, when thousands of people fled Frontera Comalapa and Chicomuselo in fear of being recruited, disappeared or killed.

In a complex task, Frayba was able to count the displacement of 2,000 people from Frontera Comalapa from 2021 to 2022, a figure that increased this year when another 3,500 inhabitants also fled.

“The Council (State Council for Integral Attention to Internal Displacement of the State of Chiapas), which legally must attend to this situation of displacement, does not do much more than bring food boxes, but in recent months it has not been seen that they have been acting in response to this situation. People go by their own means to look for their family networks, because there is no state action,” explains Lomelí.

Entrapment and recruitment

In the localities where criminals converge, there is also an increase in crimes such as extortion and extortion charges, which are not yet seen in other areas of the state, and which involve young people in their networks.

In the recent report “Childhood in the face of criminal violence” the civil association Melel Xojobal emphasizes the recruitment of adolescents between 12 and 14 years of age who live in the areas where the cartels operate.

These groups assign the adolescents tasks such as running errands, selling and transporting drugs, recruiting other young people, surveillance, coyotaje, confrontations with rivals, gangs or contract killings.

In the case of women, they work as cleaners, waitresses in bars or canteens, or are victims of sexual exploitation. “It is common for children and adolescents who are part of these groups to be used for high-risk activities that endanger their lives and integrity or that could lead to their arrest,” says Jennifer Haza, director of the organization Melel Xojobal.

He explains that the current phenomenon is reminiscent of the age-old process of enganche, in which farmers deceived workers by generating debts in order to force them to work in exploitative conditions.

In 2021, the Network for the Rights of Children (Redim) estimated that in San Cristóbal de las Casas alone 2,507 children and adolescents are at risk of falling into the hands of delinquents, while nationally the figure is 64,473.

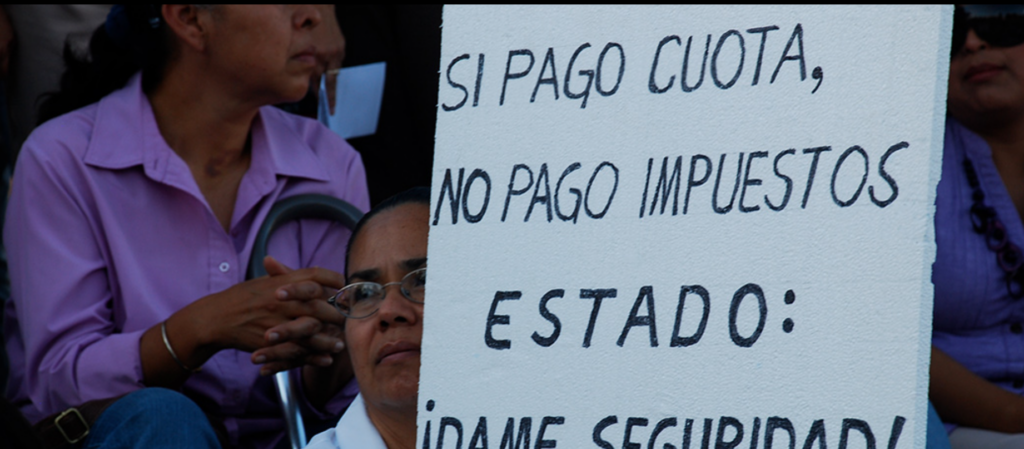

Protest in Nueva Palestina due to organized crime violence and failure of authorities to act. 2023.

New routes

The disputed territories are mainly part of at least three corridors created for the trafficking of people, drugs and arms, says researcher Lomelí. The best known is the Pacific corridor, along the coast and the main route for migrants.

The second corridor covers the highlands and highlands, and the third is in the northern zone and connects with the jungle. All three intersect in the Metropolitan or Central zone of the state.

Among the most recent complaints is that of community members of the Nueva Palestina community, located in the Selva zone, who have been affected by the blockades and surveillance carried out by the cartels at crossroads and highways.

Gray area

One month after the violence that provoked displacements and disappearances in Frontera Comalapa and Chicomuselo, on June 22, 2023, the singer Nayeli Cyrene Cinco Martínez was kidnapped by an armed group that entered her home in Tuxtla Gutiérrez.

Five days later, hooded people with long guns blocked the Ocozocoautla-Tuxtla Gutiérrez highway to intercept the bus where 33 workers from the Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection were traveling.

Only the 16 men on board were kidnapped as a bargaining chip to obtain the release of Nayeli Cinco. In videos disseminated on social networks, hooded men also called for the termination of three public officials of the same department.

The 16 officials and the woman, who was close to a CJNG leader, were released. “It is a sign that there is what in political science is called a gray zone: a non-public area where negotiations take place,” explained Lomelí.

In this case, the government demonstrated that it had strategies to deal with the problem. However, “curiously,” when violent events occur, the security forces are often not present in the areas, as was the case a few days ago when the Sinaloa Cartel paraded and was received by the inhabitants of Chamic, Frontera Comalapa.

When questioned about the context of the Sierra zone of Chiapas, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador minimized the problem with the argument that it is not a widespread situation, but insisted on reinforcing security with a greater presence of military personnel from the National Guard.

“But it seems like they are warned, it’s like a political game,” emphasizes the researcher, since militarization has become media containment. Meanwhile, governments continue to bet on the lack of collective memory.

Faces

This is the first of a series of five texts that Avispa Mídia will publish under the title Chiapas: Disappearing on Mexico’s Southern Border. The following publications will tell the story of people who have disappeared in recent years in Chiapas in the context of the dispute for territory between cartels, and the struggle of their families to know the truth.

Original text published by Avispa Midia onSeptember 26th, 2023. https://avispa.org/chiapas-desaparecer-en-la-frontera-sur-de-mexico/

English translation by Schools for Chiapas