Brecht in las cañadas

Luis Hernandez Navarro

On the wooden wall of a makeshift little school with tin roofs, near the community of El Naranjal, three hours from Oventic, in the highlands of Chiapas, there is a graffiti in black letters that announces: Our walls / Are not for / Oppressing or enclosing / They are for coloring / Life and freedom / EZLN.

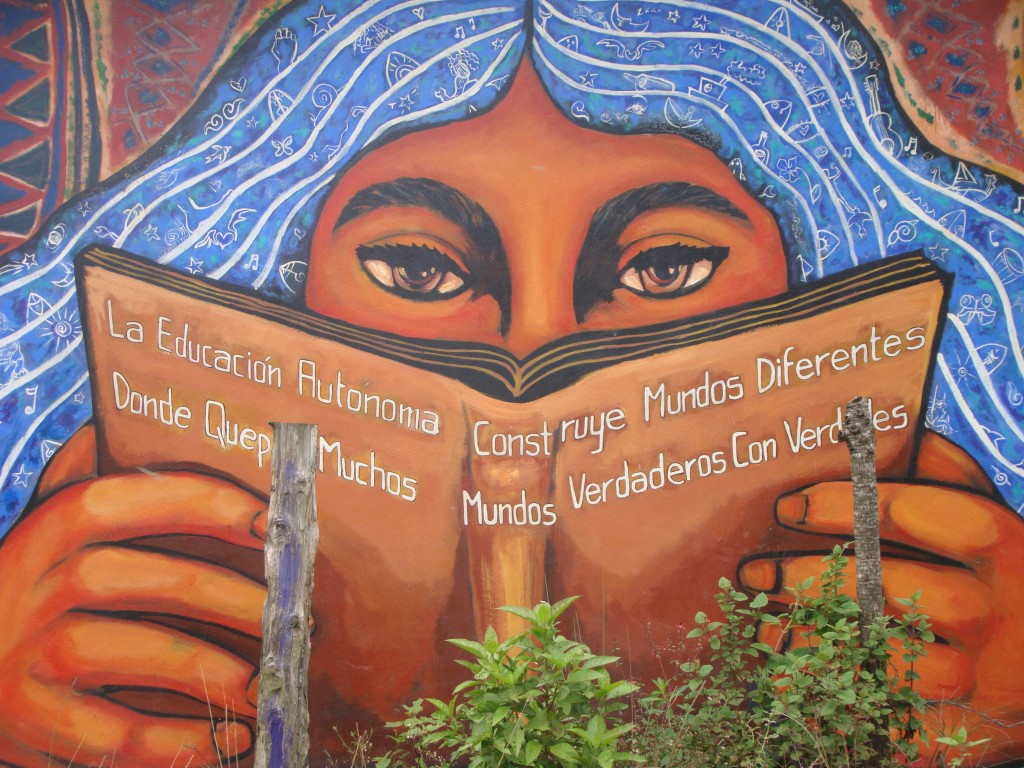

The message is one of at least 300 murals and graffiti that, hand in hand with the Zapatista autonomous rebel schools, cover the cold and arid walls of cement, adobe, wood and sheet metal of the classrooms and rebel buildings. The concert of brushes and paints wielded by children and adults of the communities on the bare walls, together with artists in solidarity, have facilitated the marking of their territory with colors of life, hope, joy and love. Forgotten by those who think they own the world, these villages find in art the reaffirmation of their own roots and horizons.

Mexican artist Gustavo Chávez Pavón, promoter of community, militant or educational muralism, disciple and comrade of José Hernández Delgadillo, was for some years part of the adventure of painting, alongside the inhabitants of the most remote communities in the mountains of Chiapas, and in some of the jungle, between four and five murals in each village.

Gustavo says that “in an afternoon of hopping wanderings and divinations in search of a secluded embrace, this adventure as a painter began, because I have the terrible passion of walking the mysterious paths as if it were a gypsy curse.”

A living colorist, creator of itinerant works in the form of banners, Chávez Pavón initially arrived in Chiapas as part of the first national and international caravan of artists. It was already evident that a great cultural movement was beginning to develop in and around the Zapatista movement.

Before, as a visual artist, Gustavo accompanied the struggle of the Coalición Obrero Campesino Estudiantil del Istmo (Cocei) and the Unión de Comuneros Emiliano Zapata, led by Efrén Capiz. In a way, he was responsible (although he did not claim to be) for converting the organization’s premises into a kind of gallery.

Once in Chiapas, Chávez concentrated in Oventic. He recalls: “That is where I was responsible for coordinating. From there, my compañeros would take me to different communities and schools. The mission would be to paint from one to four or five murals, depending on the needs of the community. It was a huge job. It was collective work, everyone’s work. Wherever I went, the compañeros were already organized. There had already been assemblies and designated commissions. We knew who was responsible for the food and where we were going to sleep. The children with whom we were going to work were already ready.

“We could work from 6 in the morning until 11 at night. The whole community participated. They welcomed me. It was my role to give a basic workshop. I taught how to use the brushes. How to hold them. I would bring notebooks, pencils, paints. I would tell them how to create images. We would discuss what images to create, what could be put on that wall. But, to say what we wanted to say, sometimes it didn’t fit on one and we would go to another. It was very exhausting, but since the atmosphere was festive, we didn’t feel the fatigue. Sometimes we had to illuminate it [our work] with torches or bonfires.

“The joy was powerful, the desire to create, the delight. The creation was everyone’s. Everything was done collectively. Everything was done collectively. We used colors that give hope and reinforce collective belonging. When we discussed with the adults which images should go on the wall, the children got ahead of us, and started painting. They are tremendous artists. The children inspired us. Many children became painters. They paint paintings.”

According to Gustavo, a great collective was formed, which was being given a face. The communities were happy. He left the autonomous primary school of Oventic for Palestine, convinced that dignity must be exported. They “entrusted him to tell them that their struggle is our struggle.” Muralism continued to flourish with artists from the communities, now without him. Convinced that “we must make murals to free ourselves from the walls,” on the walls of shame shot at by the new apartheid he painted “Long live the EZLN!”

The celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Zapatista uprising in the community of Dolores Hidalgo shows that Zapatismo marks its territory not only through the multicolored corn that sprouts from the walls of its classrooms, but also through theater, dance, music and photography. They dream collectively, as they work collectively and struggle collectively. In the words of Subcomandante Moisés, in the celebrations “the property must be of the people and common, and the people must govern themselves.”

In good company with Bertold Brecht, they refuted the claims of those who feel obliged to tell them what to do and how to do it. With a spectacular performance, they left those who announce (as many others have done throughout the last three decades) the desertion of their bases, prophesize their imminent siege and annihilation, and ignore the centrality of their proposal to struggle for life and explain their successes in the construction of autonomy as the exclusive result of solidarity and not of the development of their own forces, holding the bag.

Demystifying individual production, just like those muralist children who over the years became painters, the Zapatistas have made inroads in the artistic spheres during these decades, forming new generations of actors, dancers, musicians, poets and photographers. With the weapons of aesthetics they have shown – as they demonstrated this year-end – that, from an anti-capitalist perspective, they change the world and control their territory based on their identity, hope and cohesion. Dignity, as we know, is subversive.

Original text published in La Jornada on January 2nd, 2024. https://www.jornada.com.mx/noticia/2024/01/02/opinion/brecht-en-las-canadas-3023

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.