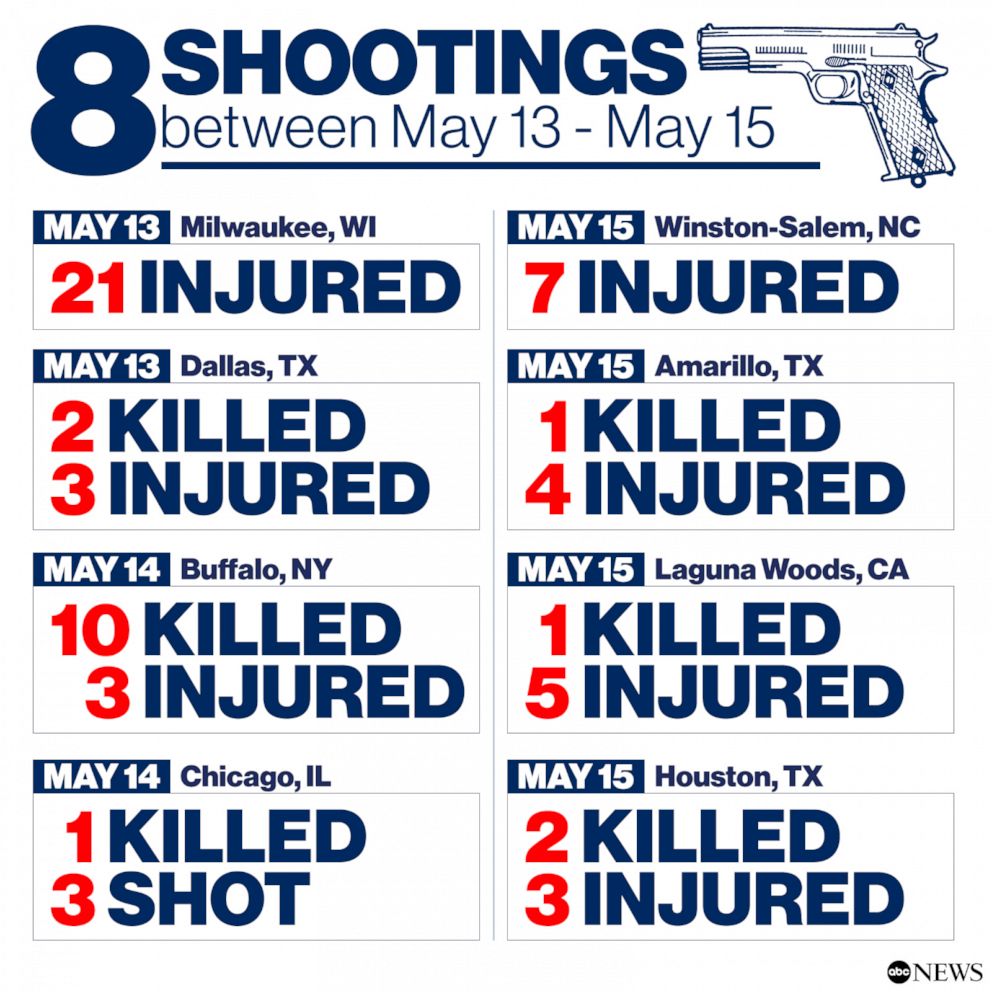

Last Saturday, a young man 18 years-old shot 10 people to death, and injured three more —the majority of whom were African American— in a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, motivated by the idea that in the United States there is a plan in place to replace the white european population with blacks and immigrants of various ethnic backgrounds. The mass-shooter live-streamed his crime in real-time on the Internet and declared himself a white supremacist and fascist when brought before a judge.

Episodes like this are shockingly common in our neighboring country and express an ingrained violence in countless citizens, as well as the prevalence of abominable racist beliefs in significant segments of the population.

A sign of the times, the explosion of social networks and the presence on them of ultra-right wing conspiratorial content make possible the trivialization of these massacres, their dissemination on specialized video game platforms and the feedback between the protagonists of hate crimes, as made evident by the Buffalo killer, who conceived of his raid as a tribute to perpetrators of other mass-shootings.

But beyond the ideologies and the technological uses, there is an underlying problem in the United States: the belief that problems both real or imagined — like the conspiratorial theory of population replacement — can be resolved through violence and murder.

That idea, which has an unfortunate expression in the elevated number of homicides in the United States, finds a deplorable parallel in Washington’s global policies, which place it as the primary planetary protagonist of wars and armed conflicts.

Another unavoidable aspect of this phenomenon is the pro-gun mentality that dominates the a good part of the society of our neighboring country, in which there are more firearms in the hands of civilians than there are inhabitants. The free trade in arms to the north of the Rio Grande is, furthermore, an undeniable factor in the criminal violence suffered in Mexico, whose criminal groups are easily supplied with handguns, assault rifles, and high power weapons of war— like the Barrett rifle— in the U.S. market.

That is not, certainly, the only way in which the United States exports violence to our country. One of the obstacles to punishing those responsible for violent crime in Mexico is the number of Mexican criminals in the neighboring country that have benefitted from the witness protection program, such as the case of Dámaso López Serrano, El Mini Lic, identified as the mastermind of the homicide of Javier Valdez Cárdenas, correspondent of La Jornada in Sinaloa, who was executed May 15th, 2017 —five years ago now— in his birthplace of Culiacán.

In conclusion, it is impossible to analyze the phenomena of insecurity and criminality in Mexico without taking into account its proximity to a nation that is as sick with violence as it is powerful, and whose disease infects other nations in many ways.

This article was published in La Jornada on May 16th, 2022. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/05/16/opinion/002a1edi English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas.