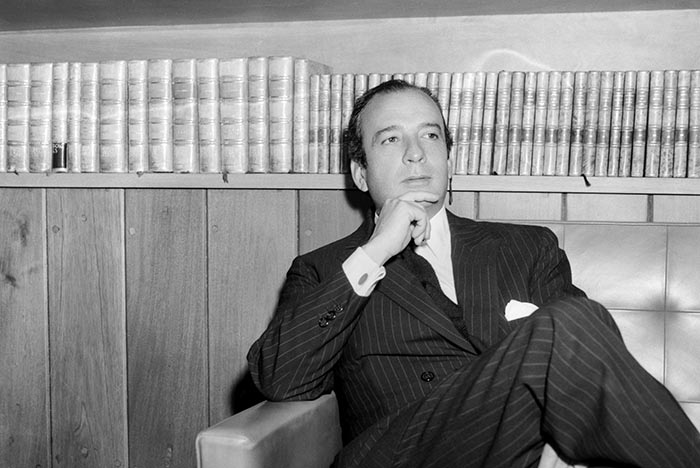

Luis Hernández Navarro

They were difficult days. The Corpus Christi massacre was a huge open wound and the dirty war was spreading throughout the country. In a meeting between President Luis Echeverría Álvarez and UNAM Rector Pablo González Casanova, the President warned him:

“Pablo, my informants tell me that you usually walk alone at night in University City. Be careful that nothing happens to you.”

Undeterred, Don Pablo replied: “Don’t worry, Mr. President. If something happens to me, the kids will know how to respond.”

A legacy of those days of threats and provocations, Dr. González Casanova developed the habit of always sitting with his back to the wall and, preferably, with his eyes on the door. He explains this habit as a result of his astigmatism and the discomfort caused by receiving direct light in his eyes.

Don Pablo was Rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) between 1970 and 1972. He did not want to become one. His candidate was the chemist Manuel Madrazo. “I never strived to be the director of anything, except for the Institute of Social Research,” he says. “That’s where I really wanted to be. One of my strengths, which seems like a virtue, to resist the political career, was that I really liked research.”

With the echo of the student-popular movement reverberating around the country, his destiny was different. “The Board of Governors appointed me to succeed the magnificent rector Javier Barros Sierra. Late at night some members of the Board came to visit me to tell me the news. I was very surprised because I was with Madrazo. The next day he came to congratulate me. I told him: ‘I want you to be Secretary General.'”

In his inaugural speech, he pointed out that he was assuming a transitional responsibility, because “first and foremost, we are or will be professors, and management positions are a passing phase of our university life. And he added: “the true professor is the one who continues to study and the true student is the one who learns to teach. A university government implies the use of reason, and the example of conduct. If it is not to be a romantic and illusory fiction, it needs to be a government in which all share responsibility.”

His vision of the democratization of education combined the opening of higher education to larger and larger numbers of students, and greater participation in university responsibility and decision-making by professors and students. And, as part of UNAM’s mission, it emphasized teaching dissent.

When he assumed the rectorship, 68 university students, polytechnic students and popular leaders were imprisoned in Lecumberri for their participation in the 1968 movement, sentenced to lengthy prison terms for the most wide-ranging crimes. Their legal processes were full of numerous and serious irregularities.

On November 13, 1970, a little more than six months after taking office, Gonzalez Casanova demanded an Amnesty Law for the detainees, stating that “the liberation of the imprisoned professors and students was of concern to us as university students.” To justify the need for its enactment, instead of getting into a debate on the legal order, he decided to appeal to the strongest republican tradition, that of Juarez, and to reasons of national security. “The University,” he said, “has the duty to point out the uneasiness produced among its students and professors by the process against their fellow students.” And “uneasiness, anxiety, doubt in the face of the law, are a sign of insecurity, which does nothing to benefit the healthy development of the nation.”

The demand for an Amnesty Law was joined by UNAM directors, intellectuals and Bishop Sergio Méndez Arceo. On November 18, a multitude of university students mobilized in support. Prominent figures of the regime opposed it, but also some protest committees, such as the Physics-Mathematics Committee of the IPN and the Political Sciences Committee of the University.

On June 10, 1971, a student mobilization in support of the autonomy of the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (UANL), suppressed by the government, was savagely repressed in Mexico City by grenadiers, police and shock groups, referred to as halcones. A wave of indignation and rage arose among the capital’s youth and shook the UNAM.

On May 31, Dr. Gonzalez Casanova spoke out publicly in defense of the UANL. “When university autonomy is affected,” he warned, “the constitutional order undeniably suffers.. When the autonomy of the University is violated, the autonomy of the other universities is violated, as well as the nation’s own legal system. When university autonomy is attacked through political, police or military measures, open or veiled, the foundations are laid for an unconstitutional regime of force.”

Those were years of tumultuous confusion. In the midst of this climate of turmoil, the seizure of the Rector’s Office took place. Under the pretext of promoting the automatic admission of the normalistas (student teachers) to the Law School, a small group led by Castro Bustos and Falcón threw the Rector out of his offices and took over the building. When the problem seemed to be on the way to being solved, a strong conflict erupted over the unionization of university workers.

“It was a very hard situation” —recalls the former Rector— “especially for those of us who thought of ourselves as leftists. The rights of the workers had to be respected, but, on the other hand, there was the unity of the institution. Most of the members of the University Council were not in favor of the idea of allowing unionization. We made several projects. To the point that I was told that either I granted the exclusion clause to Evaristo Pérez Arreola and company or they would not consent. I defended the line that the Mexican Communist Party had defended all my life until that point: not to allow the exclusion clause that empowered union leaders to fire workers who were not loyal to them.”

On December 7, 1972, faced with the imminent entry of the police into the institution, Don Pablo resigned. He was in the Rector’s Office for only two years and about nine months. However, in that experience lies a good part of the seed to recreate UNAM.

This article was published in La Jornada on February 11th, 2023. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/02/10/opinion/015a2pol

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.