By Ana de Ita*

The current government decreed the end of neoliberalism but Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life, in English), its main anti-poverty program, maintains the targeted and conditional subsidies that characterized the previous governments.

Pronasol during the Salinas administration eliminated generalized income or consumption subsidies and assigned them only to individuals with the most need according to its measurements.

Sembrando Vida’s budget for 2021 is almost 29 billion pesos, much higher than other programs that reach the countryside. As such, the recurring question of campesinos1 from various regions is, how does the government decide who can enter the program? This year’s rules of operation define the target population as those living in rural locales in municipalities that are socially underdeveloped. The reasons for leaving out 12 other states in which there are localities which are underdeveloped are not known.

The program has a clear political bias, such that, despite a discourse that refers to subjects of legal rights, it is openly used to buy [political] wills. This way, the 2021 rules of operation determine that the 79 municipalities affected by the Transisthmic Corridor would participate in the program. Many of these municipalities have lower degrees of social development than others and have been left out of the program. For example, chinanteca communities with a high degree of marginalization (according to government) have seen their incomes diminished substantially by subsidies; as the Prospera program was eliminated, the scholarships for children were reduced and they weren’t included in Sembrando Vida.

At the community level, the program produces stark social distinctions, for which the Oaxacan communities have christened it Sembrando Envidia (Sowing Envy). The program is destined for some members of the community but not all. For example, in one community of the Huasteca region of Veracruz, of 200 community members 25 could participate; in the mountain region of Guerrero of 600 community members 60 were included. In Chiapas, 5 or 10 people per community are participating. Those who participate in Sembrando Vida receive 60,000 pesos annually, while the Production for Wellbeing program gives its participants 4 thousand pesos a year to farmers who have an equal area of 2.5 hectares2. The subsidy, given out on an individual basis, is intended for consumption and is not invested in projects or services that improve the quality of life of the community. An increase in alcoholism, litigation, and violence against women has been documented.

Without a doubt, the most damaging effect of the program is the destruction of the community fabric and the organizational decision-making structures. The indigenous and campesino communities in Mexico have an extensive tradition of collective territorial management, based on social land ownership and the assembly as the highest authority. The Sembrando Vida program is intentionally undermining these structures that grant a certain degree of autonomy to the communities. The so-called Peasant Learning Communities that include 25 members of the program and are tutored by social and productive technicians, are in charge of sharing information and defining the agenda to address the important issues in the communities. The campesinos that participate in Sembrando Vida have time conflicts with participating in the assemblies and committees of their own community, since they have to respond to the demands of the program. There is no accountability for the participants to the Assembly of the Ejido3or the Community, even though they are members of ejidos or communities, and despite the fact that the ejido or community has lent them the land in order to participate.

Members of the Peasant Learning Communities are gaining power with respect to the institutions, and in fact can assume representation of the communities in order to speak in their name.

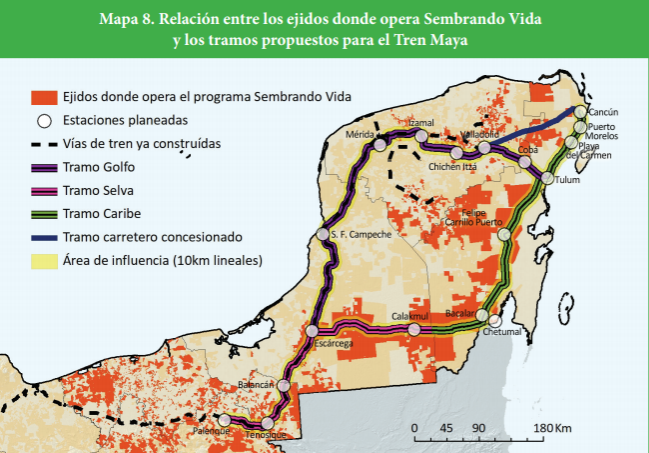

The program seeks to create a parallel organizational structure to the community organization, one that responds to its interests. Once President López Obrador has classified all campesino organizations as corrupt, the program purports to create cooperatives. It is difficult for the members of these groups to participate in social resistance movements, such as those confronting the government megaprojects, or the extractive interests of companies. Hence, the coincidence between the new outline of the Mayan Train and the localities with Sembrando Vida, and the express instruction to include the municipalities of the Trans-Isthmic Corredor.

The alternative that several communities and organizations propose is that the program be directed to the communities and not to individuals, and that it look to strengthen the autonomous structures. However, that would fail to fulfill the objectives of clientelism and political control that seem to be the priorities of the government.

* Director of the Center of Studies for Change in the Mexican Countryside.

This article was originally published in Spanish by La Jornada on January 21, 2021. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/01/21/opinion/020a2pol This English interpretation has been re-published by Schools for Chiapas.

Footnotes

- Campesino translates in English as peasant, or from the country. In Mexico and Mesoamerica, the campesino is typically a small farmer whose production, at least, in part, feeds her/his family. We choose not to translate it in order to familiarize our readers with the deep and vast knowledge of a rural population whose stories make up the rural social structures and movements throughout Mesoamerica.

- 6.177 acres.

- Ejido An ejido is an area of communal land used for agriculture in which community members have usufruct rights rather than ownership rights to land, which in Mexico is held by the Mexican state. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ejido)