Weakening of the environmental sector, advance of illegal logging and violence against defenders.

The short budget for the environmental sector and the incomplete re-design of the Semarnat has stricken protected natural areas and forested regions. Violence against Earth defenders and megaprojects pushed by the federal government continue. Some achievements: The Escazú Agreement1 entered into effect and the first steps were taken to prohibit the use of glyphosate.

Text: Thelma Gómez Durán / Mongabay Latam

Photos: Robin Canul, OPUDEVER, CONANP/PNCS, Rodrigo Medellín, Natura, Ginnette Riquelme, Everardo Chablé, Comité en defensa del bosque El Nixticuil, Gobierno de México, CNDH, Fonatur, Francisco Ramos, Cuauhtémoc Moreno, Roxana Romero

There are three hard facts that give us some idea of how Mexico fared in 2021, when it comes to the environment.

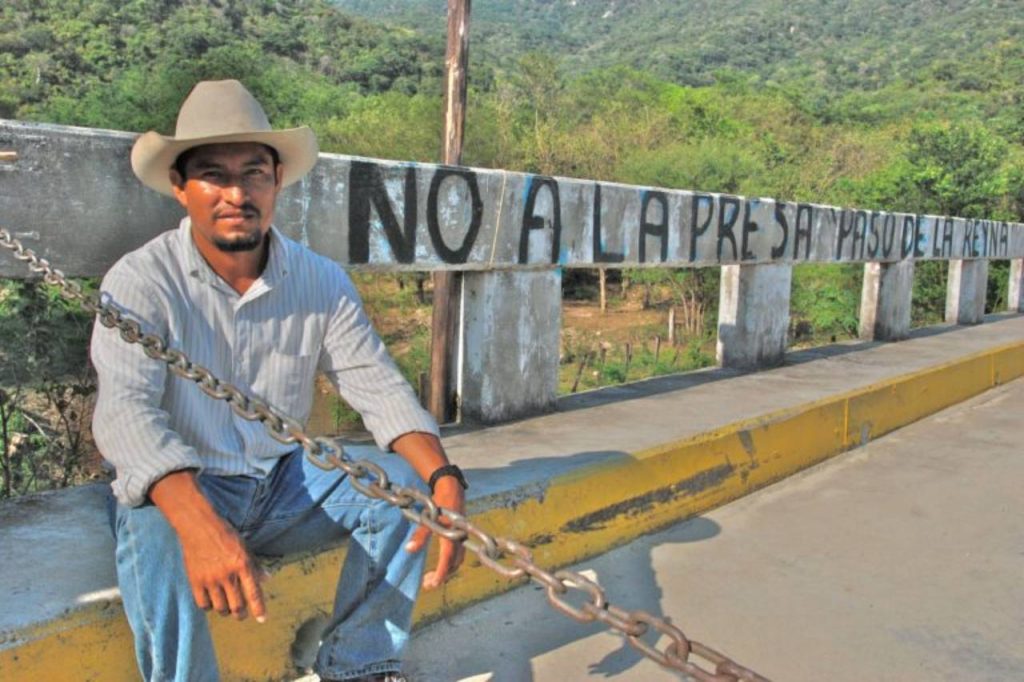

Just as the year kicked off, they killed Fidel Heras, an active defender of the Rio Verde and president of the Ejidal Commision of Paso de la Reina. This happened on January 23rd. By the time March ended, already four more residents of that community in Oaxaca had been killed.

In the first months of 2019, at the beginning of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration, scientific researchers in the southeast of Mexico warned federal and state authorities that there was a clandestine airstrip in the heart of the Lacandón Jungle. Three years have passed and the runway is still there.

Last November 22nd, in the pages of Diario Oficial de la Federación2, a presidential decree was published in which the projects and works over which the government was in charge, considered to be priority and strategic, were declared “in the interest of public and national security,” therefore all agencies were instructed to grant the necessary authorizations —including environmental ones— within the maximum period of 5 days.

Throughout 2021 that which scientists and NGO’s warned since the end of 2019 was confirmed: the environment was not within the priorities of the Fourth Transformation, as López Obrador calls his presidential term.

For scientists, forest specialists and members of NGOś, Mexico ends 2021 in the red with respect to its natural resource situation. They all agree that the tiny budget that was allocated to the environmental sector demonstrated the governmental disdain for a strategic issue. Additionally, they consider that it gives fertile ground for problems that the country already suffered, such as impunity for environmental crimes, abandonment of forest communities, and violence against the environmental and territorial defenders, to grow.

Photo: Courtesy COPUDEVER.

The Concern: Dismantling of the Environmental Sector

Since this six-year term began, the environmental sector has been one of the hardest hit. In 2021, 31.348 billion pesos were allocated for the entire sector, just a little more than the 28.9 billion pesos (a little more than 1.368 billion dollars) than one of the main government programs, Sembrando Vida, received.

Key agencies for protecting natural resources and combating environmental crimes received minimal resources. For example, the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (Conanp) had a budget of 866,383,000 pesos (around 41 million dollars), an amount that is equivalent to allocating around 9.6 pesos (less than 50 cents) to each of the 90 million hectares of national territory under some category of protection.

Calculations made by members of the Network of Environmentalist Youth show that for every peso that is not invested in protected natural areas, between 100 and 400 square meters of forest canopy is lost. “As of 2016 (during the term of Enrique Peña Nieto) when the budget of Conamp was substantially reduced, the loss of forest cover exploded,” explained Aldo Muller, environmental economist and member of the Network.

The Federal Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa) was another of the hardest hit environmental agencies: it had 52 million pesos less than in 2019, and received 742,103,000 pesos (around 35 million dollars).

The low budget allocated to the Conanp and Profepa has caused an institutional absence in protected natural areas, confirmed Doctor Rodrigo Medellín, researcher at the Institute of Ecology at UNAM. And with that, species of flora and fauna that already in fact had problems are placed in an even more vulnerable situation. In addition the biocultural processes of these areas are damaged — the relationships of the ecosystems with the well-being of the local communities.

As an example, Medellín tells of what happens in the El Tepozteco National Park, in Morelos, where building is prohibited, but where houses are being built, some of them close to the Cueva del Diablo (Devil’s Cave) a site where the greater maguey bat (Leptonycteris nivalis) mates. To date, no other mating site for this species is known. So, the future of this bat depends, to a great extent, on the conservation of this cave. “We have told the federal authorities, the local ones, the National Guard; they all say it is very serious, but no one does a thing. No one enforces the law. There is total impunity,” the researcher claims.

The budget cut wasn’t the only problem that shook the environmental sector in 2021. Lucía Madrid, graduate of Environmental Politics from the University of Cambridge and specialist in integrated landscape management, remembers that since 2020 the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) began a re-design that still hasn’t come together, and which further weakened the agency.

Semarnat underwent personnel cuts, leaving state offices without a head, and until December 2021, there were no internal rules published, so the new sub-secretariat and general management does not have clearly assigned responsibilities. Among the consequences that this has created is a delay in attending to all kinds of procedures, among those related to forest management, “which disincentivizes legal management of the forests and violates the rights of forest communities,” Madrid emphasizes.

The Critical Issue: Loss of Forest Coverage

For doctor Rodrigo Medellín one of the greatest environmental catastrophes that the country experiences today is the loss of forest cover in the Lacandón Jungle, in the southeast of the country.

The expansion of the african palm plantations and cattle ranching, agrarian conflicts that have gone unresolved for years, the invasion of protected natural areas and the presence of organized crime are some of the activities that are destroying the Lacandón, mention the researchers that work in the zone, who are trying to save species like the jaguar.

There are still no data that show how many hectares of forest cover the national territory lost in 2021. The available information to date is not hopeful. Mexico lost 300 thousand hectares of tree cover in 2020, according to the analysis of satellite images done by the University of Maryland and published by the Global Forest Watch platform.

Additionally, there have been 122 critical zones identified in the country, in which illegal logging, timber laundering, changes in land use, man-made forest fires, and the presence of organized crime, according to data presented by Semanarat itself last October.

In light of this situation, María Luis Albores, head of the Semarnat, presented a “strategy against deforestation and illegal logging,” which is based on the prevention, inspection and verification of sawmill, as well as intelligence work…with the aim of being able to criminally prosecute those responsible for the crimes.”

Lucía Madrid explains that it is not possible to have the same strategy to address illegal logging and deforestation because, “they are distinct phenomena, carried out by different actors.” Deforestation, she comments, has to do with changes in land use and it is related to production chains like cattle ranching, industrial agriculture, real estate development and megaprojects. “In Mexico,” she insists, “there is no concrete strategy to stop deforestation. Nor are there sufficient resources for the unit that monitors deforestation, which doesn’t allow for timely decisions to address the phenomenon. And yet, deforestation is one of the primary socio environmental problems in the country, that devastates 250,000 hectares of forest a year.”

Photo: Ginnette Riquelme.

On more than one occasion, the head of the Semarnat has presented the achievement of having signed an agreement with representatives of the Mennonite community of Campeche, in which they commit to stop deforestation in the Mayan jungle.

For years, beekeepers have filed complaints against the Mennonites for having converted thousands of hectares of Mayan forest into soybean fields.

The agreement between the Semarnat and the Mennonites “generated a great deal of anger in the the Mayan communities of Hopelchen,” indicated Jorge Fernández, of Equipo Indignación, an NGO that works in the Yucatan Peninsula. The anger, he explains, is because the Mennonites continue the deforestation and illegal planting of transgenic soy.

In October of 2021, Greenpeace and the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (Cemda) filed a complaint before Profepa for the sowing of soy and corn that is likely to be transgenic in the communities of Hopelchén, Campeche.

Photo: Everardo Chablé.

While the country loses forests, jungles, mangroves, pastures and species of flora and fauna, the 2310 + communities that carry out sustainable forest management face increasing challenges: red tape, tax burdens, the presence of organized crime in their territories, forests where pests and disease are exacerbated by climate change, and a significant decrease in the support that they receive from the National Forestry Commission (Conafor).

“The chaos that has been caused by the budget shortfall and the weakening of the Semarnat carries with it the advancement of illegality, because at the same time, many regions are suffering pressure from organized crime that seeks to control everything related to forest exploitation,” explains Lucía Madrid, who also makes up part of the Mexican Civil Council for Sustainable Silviculture (CCMSS).

José Iván Zúñiga, of the World Resources Institute (WRI), points out that the lack of investment in communities that carry out sustainable forest management opens the door to other problems: “If you don’t have forest management,” he warns, “you don’t have firebreaks or timely and trained attention to forest pests and diseases.”

The fire issue is already evident. By April 2021, fire had already affected just over 127,000 hectares, almost double the 69,000 hectares damaged during all of 2019, according to Conafor reports.

Credit: Committee in defense of El Nixticuil forest.

The Controversy: Red Flags of Sembrando Vida

In March of 2021, el WRI published the report, Analysis of the impacts on forest cover and mitigation potential of the Sembrando Vida parcels implemented in 2019, that revealed relevant information about the possible negative consequences of one of the signature social programs of the federal government.

Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life) grants five thousand pesos monthly to each “planter,” as they call participants that adopt agroforestry systems— the planting of corn, annual crops, fruit and timber trees — in their parcels. On more than one occasion, López Obrador has said that it is a program of reforestation, a classification not shared by forestry experts.

Since the launch of Sembrando Vida, in February of 2019, it was reported that in order to enroll in the program, some planters logged the trees on their acahuales3, as the plots are called, which had been used for agriculture or cattle ranching, but now have forests or jungle in recovery.

The WRI study documented that in 2019, as a consequence of Sembrando Vida, 73,000 hectares of forest cover were lost. But it also found that it could have a yield of timber trees on at least 300,00 hectares that previously were used for agriculture.

“With our analysis we estimate that the program can have a positive result in terms of carbon sequestration,” explains José Iván Zúñiga of WRI. However, he also clarifies that in order to achieve a positive balance, in terms of carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation, it is essential that the 400 hectares planted with timber trees be maintained for at least 30 years.

Zúñiga also warns that Sembrando Vida has several red flags. For example, management programs have not been implemented on the properties where timber trees have been planted, which are essential if the timber produced on the land is to be legally harvested in the future.

Land tenancy is another red flag; “in many cases, —Zuñiga explained— “we have found that the parcels used by the planters are rented, loaned or were taken out of the community common area (ejidos). And so, there is no guarantee that these hectares planted with timber trees are going to be maintained with time.”

In addition, according to the current law, the forest plantations have to be registered the Semarnat and Conafor in order to be legally harvested timber. The plantings that were carried out in 2019 were not registered and the deadline for doing so expired in 2020.

“The program should not be criminalized. It needs to solve these problem areas to be able to guarantee permanence over time of agroforestry timber systems, and Sembrando Vida could have an impact on carbon capture,” Zuñiga points out.

The Serious Issue: Relentless Violence Against Defenders

The assassination of Fidel Heras, the President of the Ejidal Commission of Paso de la Reina, in Oaxaca, which happened in January of 2021, was the notice that violence against environmental and territorial defenders which had been going on for years, would not stop.

In 2020 alone, 30 murders of environmental defenders were recorded in Mexico, according to the annual report of Global Witness, which means an increase of 67% compared to 2019, placing the country in second place in this unfortunate list, after Colombia.

In 2021, the violence continued unstoppable. En Paso de la Reina, there were five murders, that of Fidel and another four residents of the community that since 2007 were organizing to defend the Río Verde and prevent the installation of a hydroelectric plant there. Weeks before he was murdered, Heras denounced the illegal extraction of sand from the river.

In the mountains of Guerrero, in the south of Mexico, Carlos Márquez Oyorzábal was assassinated on April 3, 2021. He was 43 years old, with four children, and was the municipal commissioner of Las Conchitas, municipality San Miguel Totolapan, a region where organized crime groups —who control the planting of heroin poppies and illegal logging— have increased their numbers and have caused the displacement of several communities.

Until September of 2021, the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (Cemda) had recorder 13 murders of environmental and territorial defenders in Mexico. The organization, which this coming March will publish its annual report on the issue, has found that in 2021, “the number of aggression against those that oppose the Mayan Train has increased, as well as those where illegal logging or the presence of organized crime in forested areas is reported,” Margarita Campuzano of Cemda states.

Opponents of the so-called Mayan Train have had to face threats, and have also seen environmental standards violated without any consequences. This year, for example, in the courts, it was demonstrated that the works began with approval of the Environmental Impact Statement (MIA). This allowed them to obtain four injunctions to stop the work But, “Fonatur and Semarnat are not complying with the suspensions. And that implies a violation of the rule of law, but also the certainty that the current administration is going all in to implement this megaproject,” explains Jorge Fernández, of Equipo Indignación.

For Fernández, what is happening with the works of the so-called Mayan Train shows that the current administration has no interest in establishing mechanisms of dialogue to listen to the communities that oppose the project, nor to those of different scientific disciplines who have warned of the consequences a project of this scale can have on an ecosystem as fragile as the Mayan Jungle.

The Mayan Train is not the only megaproject that the federal government is pushing. In Oaxaca and Veracruz, the Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is being planned, which foresees the installation of at least ten industrial parks.

In order to accelerate these and other infrastructure and tourism megaprojects, on November 22 a presidential decree was published declaring the works in charge of the government that are considered to be of “public interest and national security” to be of priority and strategic importance. In addition, all agencies are instructed to grant a “provisional authorization” within a maximum term of five days.

Although the Supreme Court admitted a demand from the National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information, and Protection of Personal Data (INAI) and suspended the part of the agreement that gave tools to officials to deny public information about the governmental projects, under the argument that they are considered of national security, the instruction to grant provisional authorization to accelerate the works continues in effect.

“The agreement tries to eliminate obligations to which the Mexican state is committed and must comply with, before granting any type of authorization for megaprojects, such as carrying out procedures of consultation and free, prior and informed consent, or the realization of prior social, environmental and legal impact studies, which are essential for indigenous peoples and others to be able to make an informed decision with respect to said projects,” the Fundar organization pointed out, one of the many voices that came out against the controversial decree.

What is Being Ignored: Climate Change

In years past, Mexico signed the Paris agreement in which it committed, among other things to end deforestation by 2030. Now in the most recent UN Summit on Climate Change (COP26), the country joined the Declaration to reverse the loss of forests and land degradation also by 2030.

But the Special Program for Climate Change 2021-2024, published last November, forecasts a loss of one million, 300 thousand hectares of forests before the end of the six-year term [of AMLO], around 216 thousand hectares each year.

“How are you going to meet a goal of zero deforestation by 2030 if in 2024 you are planning to lose nearly 216 thousand hectares? Semarnat did not make a more ambitious goal to combat deforestation because it can’t, it doesn’t have a strategy to do it,” Lucía Madrid of CCMSS, points out.

In addition, the commitments to comply with the reductions in greenhouse gases, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), that the country presented in 2020 were the same that they had in 2015. This resulted in Greenpeace filing an injunction, and last October, a judge definitively suspending the 2020 NDC.

“Without more ambitious NDC’s we are not going to advance. The country also has a commitment to generate energy from clean sources, starting in 2024, and we are very far from that. The current administration is trying to include natural gas and hydroelectric as clean energy, but from our point of view these are not renewable sources,” Margarita Campuzano, of Cemda explains.

At COP26, Mexico didn’t even sign on to the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement, which proposes stepping up the use of renewable energies and leaving behind the use of coal in energy generation. López Obrador’s administration is betting on the use of fossil fuels and as proof, there is the construction of the refinery in Dos Bocas, Tabasco, right on parcels where there had previously been mangroves, a zone which is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

The Good Thing: Launch of Escazú

The 22nd of April, the Excazú Agreement came into effect, an innovative treaty for Latin América and the Caribbean which was created to guarantee access to the rights of information, participation and environmental justice. In addition, it obliges the States to protect defenders of human rights on environmental issues. Mexico was one of the twelve countries that ratified the treaty thus promoting its entry into effect.

The Secretary of Foreign Affairs and the INAI organized working groups to disseminate the contents of the treaty and work on what Mexico must comply. The Semarnat, for its part, did not have any contact with the civil society organizations focused on implementing what was in the agreement.

“We have not been able to enter into a dialogue with the current administration. Unfortunately, the environmental issue is not a priority, it is not considered a strategic matter,” notesTomás Severino, director of Cultural Ecológica, one of the organizations promoting the regional treaty.

Photo: Roxana Romero

Those who managed to be heard, after several months of insistence, were the communities and organizations that make up part of the National Assembly of Environmentally Affected People. In July, an agreement was signed between various agencies of the federal government —Secretary of Health, Semarnat, and the National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt)– to work to address the areas where industrial contamination has caused health and environmental emergencies.

“It is an step forward that secretaries accept an recognize that there is an environmental problem brought by industrial contamination and that they should act,” says Alejandra Méndez, of the Fray Julián Garcés Human Rights and Local Development Center, an organization that works in Tlaxacala with the communities affected by the contamination of the Río Atoyac.

One issue in which Semarnat has been very active is in the prohibition of glyphosate. In December of 2020, a decree was published which ordered the prohibition of the agrochemical by 2024. The agrochemical industry did not stand idly by — Monsanto filed a legal action against the decree. So the legal battle continues.

This article was published on December 16th by Mongabay LATAM. https://es.mongabay.com/2021/12/deudas-ambientales-de-mexico-en-2021/ English translation by Schools for Chiapas.

Footnotes

- The Escázu Agreement is the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, which includes provisions for the protection and promotion of human rights defenders in environmental matters.

- A daily official publication of the Mexican government.

- Acahual is a plot of land used in diversified milpa, that lies fallow for a period of several years to decades in the management of itinerant agriculture. During this period, it is allowed to return to secondary forest with interspersed species for harvest, fruits and vines.