Leaving Oxchuc in the direction of San Cristóbal, a road opens up to the left that winds its way into a deep valley, surrounded by green mountains and covered with low clouds. The stones piled up at the beginning of the route reveal the tension in the area, with almost uninterrupted blockades when conflicts flare up.

A short distance away I see a sign that says almost everything: “We are the ex-combatants returning for our land.” The war between brothers, between families in the same communities and sometimes even within the same families — the widespread violence– is perhaps the greatest triumph of the counterinsurgent social policies that the “bad government” applies to destroy the organizations from below.

As we continue further, members of the Ajmaq Resistance and Rebellion Network and the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), explain the difficulties we may encounter along the way. They mention in particular a family a little more than a hundred meters from Nuevo Poblado San Gregorio, which usually closes the road when visitors arrive to the community, which is part of the EZLN’s support bases. They are worried because they haven’t visited the community for four months, since they had to suspend the observation brigades due to constant threats they received.

Overcast skies, leaden clouds, intermittent rain that threatens to turn into a downpour, and a road that gets worse as we approach our destination. We are greeted by a handful of middle-aged men and women, we walk towards an open and covered space from which we contemplate a beautiful panorama: shades of green in the meadow that climb up to the peaks covered with native trees.

From recovery to dispossession

From recovery to dispossession

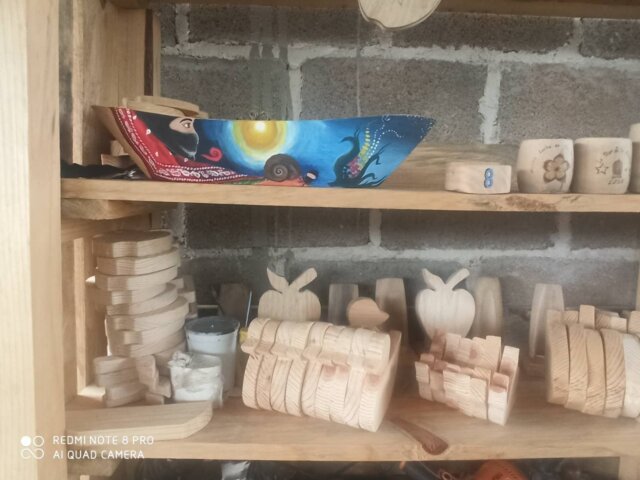

After the usual greetings, we sat in a circle in the same space where the carpentry shop is located. They make objects to be sold in the cities, to strengthen resistance and maintain the work collectives. A small multicolored boat stands out, part of the imaginary created by the Travesía por la Vida (Journey for Life) that crossed Europe in 2021.

A Zapatista comrade stands up and begins a long retelling of the history of Nuevo San Gregorio. He begins by saying that two families have left in the last few days, overwhelmed by hardship. There are only four families left, they look tired but they smile, they are enthusiastic about the visits, and the education promoter does not hide her enthusiasm.

“We recuperated the 155 hectares of the ranch on October 12, 1994,” says the compa. He recalls that there were many more families, perhaps thirty, but “many compas withdrew from the organization to receive the government’s programs and its bad ideas. Those who remained always insisted on autonomy and collective work.

Corn, beans, wheat, vegetables, peas and cattle were worked collectively, in addition to the plots of each family. “We don’t feed chemicals to mother earth,” the bases of support told us as the rain hit the rooftops forcefully, muffling the words.

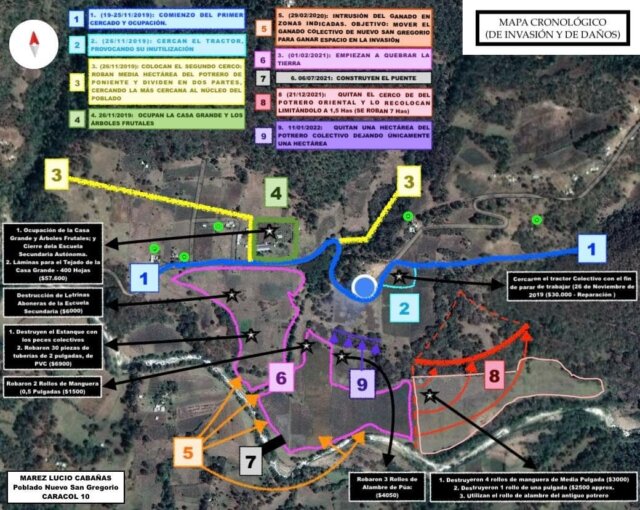

Ten villages in the area participated in the recuperated lands, who farmed it collectively. But on November 19, 2019, things changed dramatically. Some 24 families from four villages began to fence in the recovered lands, progressively putting up fences until they occupied 95% of the land, leaving only a few hectares where the four Zapatista families are clustered.

They fenced in the compas’ tractor, preventing anyone from approaching until it began to deteriorate and was eventually ruined. They occupied and then looted the secondary school that operated in what was the ranch’s main house, destroyed crops and injured cattle with machetes. They destroyed the collective pasture and the fish pond, fenced off the water well and the roads, making access to electricity, water and firewood increasingly difficult.

The 8th of September, two days before our visits, they entered the secondary school and the offices. That was the most recent aggression, but it won’t be the last; for the past three years they have been gradually looting and encircling the support base families. They are always men with machetes, batons and clubes, and some with guns. They watch them constantly, they don’t let them plant, the threats raining down even upon the people who visit in solidarity.

The Junta de Buen Gobierno “Nuevo Amanecer en Resistencia y Rebeldía por la Vida y la Humanidad” (New Dawn in Resistance and Rebellion for Life and Humanity) and Caracol 10 “Floreciendo la Semilla Rebelde” (Flourishing the Rebel Seed), brought forward three proposals to resolve the situation. The first was to work the lands in common and share the yield between the families. They did not accept.

The second was to divide the lands according to one hectare per person, in such a way that a substantial portion of the 155 recuperated hectares would be used by the invaders. They didn’t accept.

The third proposal, guided by the principle of not wanting to have violence between indigenous peoples, was to cede half of the land to them. They did not accept that either.

Destroying Neo-Zapatismo

Questions swell in our hearts. What are they looking for? If they control almost all the land except the space where the support bases are, why do they insist on harassing them when they do not represent a threat to their crops? Is there someone behind the invaders?

“In reality they don’t even need the land because they have plots in other places,” say several people. They are looking to grab more land, but that’s not all. “They seek violence, manipulated by the government. What bothers them is our resistance, our autonomy and rebelliousness, that we fight for life and not for individual interests.”

Among the invaders there is a hatred that is difficult to understand and explain. “It makes us very angry,” say the support bases, because the invaders are friends, neighbors and relatives, cousins and even brothers, former Zapatistas who fired bullets during the 1994 uprising. A hatred that cannot be explained only by the desire for material goods. There is something else that can be identified as government social programs, and now as Sembrando Vida.

The very name of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government program is a stripping away of the ways in which we anti-capitalists name the struggle. It is what capitalism does when confronting peoples who are struggling. for life. But this program has some perversions that surpass those of former governments.

The resources do not go to the ejido but to the individuals, they were individualized as a way of dividing communities and society, of allowing a greater penetration of capital in all corners of society. As we know, community and capital are antagonistic, to the point that capital needs to destroy ties and common goods in order to continue its accumulation. That is the role of Sembrando Vida.

To receive the 4,500 pesos a month from the program, each recipient must own 2.5 hectares of land.

But we have nothing, the family never had land.

There are the lands of the Zapatistas, take them. This not-so-imaginary dialogue between community members and state officials in Chiapas sums up how those at the top encourage other campesinos to become combatants against the support bases.

Behind this state scenario, there seem to be other entities, like Orcao (Regional Organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo), close to Zapatismo at the time, and Comach (Organizations for the Environment for a Better Chiapas), that promote the destruction of everything that the EZLN builds, including kidnapping and assassinating support bases and autonomous authorities.

To a large extent this explains the hatred, the “envy” as the bases of Nuevo Poblado San Gregorio say. The EZLN is an obstacle, a material and symbolic impediment to receiving government programs.

Before it was somewhat different. The families that wanted to receive official programs had to leave the autonomous school to go to the government school; they had to leave the EZLN to receive aid in money, food or sheets and blocks for the houses. If they did not leave, they received nothing.

Now it is much worse. To receive anything, they must fight against the support bases, invade their lands, destroy what they have built. Become their enemies. Before, they could withdraw and maintain a certain neutrality, although their lives were wrecked by not working land, and engaging in drunkenness. Now neutrality is not possible. This is one of the main reasons for the war in Chiapas.

If they have to fight against Zapatismo, they can ally themselves with anyone who uses violence, from Orcao to organized crime, structures that are becoming increasingly similar in their ways and in tune with their objectives. There is no longer a difference between the “social organizations” that use violence against the people, and those of the narco and the paramilitaries. In the same way, there is no longer any difference between Morena and the PRI, in their political culture and their desire to remain in power.

Dignity does not depend on numbers

“When they destroyed the collectives, we created new ones.” The carpentry collective makes chairs, tables, pots and other objects with hand and power tools. Other collectives make embroidery and pottery, they have a small shop that sells to visitors or send to the cities. Now they have started to make pieces with bamboo. They are always seeking and creating in spite of the difficulties.

“We don’t feel small. Our joy comes from the art we are making, which reaches farther than bullets, because what you see was taken to Europe. We continue to make figures, creating life and not death.” The compa speaks slowly, moving forward like a snail.

They relate that there are similar threats in other towns grouped in Caracol 10, as has been happening in Moises and Gandhi. “The communal labors are the only alternative, they are a new way of being able to live.” The reflection goes further, along the same path. “I no longer worry about what was taken from us, but about carrying on with what we have.”

A philosophy of life that has profoundly spiritual features, which does not revolve around material goods because it places living beings, human and non-human, at the center. “We are guardians of the earth, not its owners. She is going to own us, because that is how we are, no one is eternal. The earth takes care of us and protects us.”

After the meal, which they serve us with care and cook with dedication, it is time to say goodbye, which, as always, stretches out the moment of parting. As soon as we set off, a small, poor woman insults us and a boy runs, machete in hand, to tell them to cut us off, as they often do to prevent further visits.

We narrowly escape that sticky and cruel hatred, which leaves a feeling of rage and sadness for the human condition in our souls. We vent the desire for revenge with the farewell phrase of the support bases: “We do not fight to kill.”

You can read the respective communiqués at: https://redajmaq.org/es/visita-al-caracol-10-y-nuevo-san-gregorio and at

https://frayba.org.mx/amenazas-y-agresion-durante-documentacion-en-el-poblado-de-nuevo-san-gregorio. Translations by Schools for Chiapas.

This article was published in Desinformémonos on September 19th, 2022. https://desinformemonos.org/mexico-ii-nuevo-san-gregorio-la-dignidad-de-los-que-persisten/ English translation by Schools for Chiapas.