by Raúl Zibechi

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing war between powers is having profound effects on critical thought and movements, but in divergent ways in the North and in Latin America: differences and distances in the ways of conceiving and practicing anti-capitalist transformation, as well as the ways of conceiving reality, are deepening.

In the history of critical thought, war and revolution have been knotted to such an extent that it is almost impossible not to relate the latter to the former. Maurizio Lazzarato’s recent book, War or Revolution. Because Peace Is Not An Alternative (Tinta Limón, 2022), reclaims the concept of war that, in his opinion, had been expelled by critical thought in the last 50 years.

The core of his work returns to Lenin’s 1914 proposal, in the sense of transforming the imperialist war between peoples into a civil war of the oppressed classes against their oppressors. He maintains that the great problem has been, in tandem, the abandonment of the concept of class, as well as that of war and revolution. And he asserts that the present conjuncture is very similar to that of 1914.

This is a first and decisive difference: on this continent, war is present and undeniable, particularly against native and black peoples, peasants and inhabitants of the urban peripheries. The wars against drugs and the appropriation of territories for extractivism are just the latest version of a centuries-old war against the peoples.

However, the central aspect to be emphasized is different. The peoples are facing the wars against them asymmetrically, not because they are pacifists, but because a long experience of five centuries convinced them that in order to survive as peoples they must take other paths.

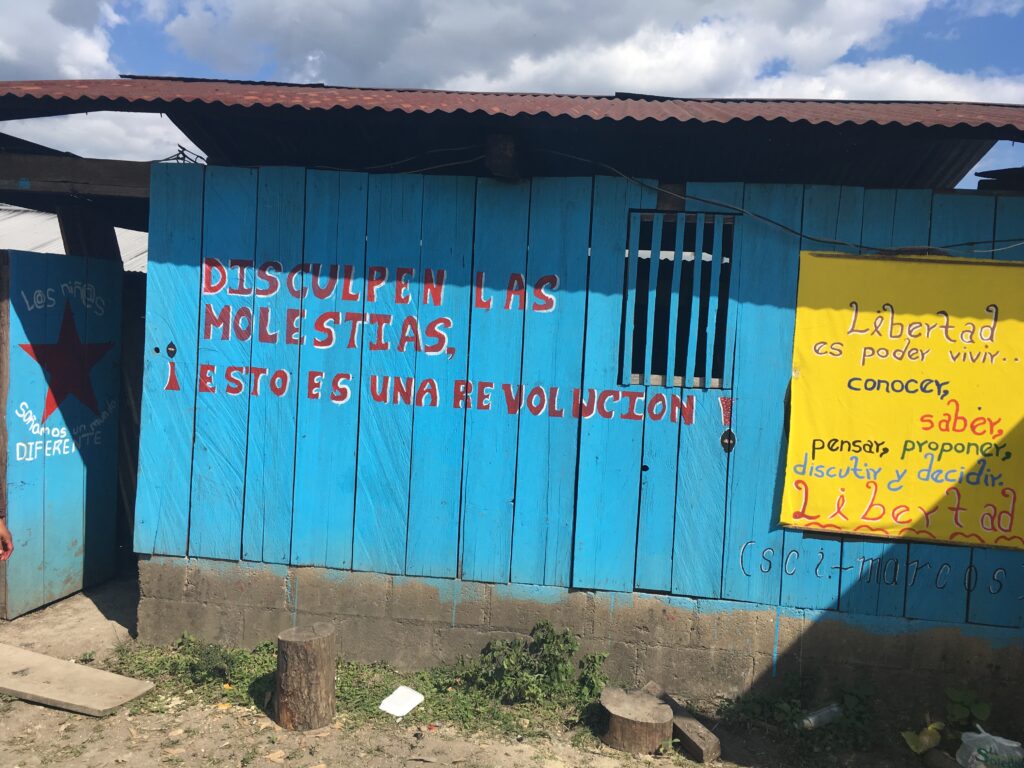

Zapatismo has managed to break the ties between revolution and war and, in the same process, has stripped the revolution of its statist trappings, leaving its core intact: recovery of the means of production and exchange, creation of new social relations and non-state powers. Autonomies are the way, both to resist the war of dispossession and to affirm themselves as self-governing peoples.

It is true that the European and Latin American lefts have been left without politics, without concrete proposals in the face of war. But the peoples of this continent, experts in surviving wars of dispossession, are taking unprecedented paths, as are the Mapuche, the Nasa and Misak, the dozens of Amazonian peoples and the black and peasant peoples to confront this war. They are beginning to place autonomy in a central place in their constructions and reflections, something that apparently escapes the intellectuals on both sides of the ocean.

An additional sample of this Eurocentrism that pretends to speak for the oppressed peoples, is when Lazzarato points out that the great merit of the Russian Revolution was to open the road to the revolution of the oppressed peoples. He neglects nothing less than the Mexican Revolution and the first Chinese revolution. The most profound processes are born in the peripheries, and much later expand towards the center.

It is not true that the clearest position in relation to the war is still the revolutionary socialist one as during the First World War. It was very valuable at the time, for the working classes of Russia and Europe. It failed in China, where the communists took quite different paths, creating Red bases liberated by the peasant army, a process followed by other peoples of the South.

Eurocentrists believe they understand what is happening in Latin America and consider our struggles as laboratories that would confirm their illusions. Some of them feel theoretically disarmed in the face of war, but do not want to learn from the experiences of peoples who have survived five centuries of massacres and exterminations. They only pay attention to the theoretical production of the academies and from the left that refers to the nation-states, that is, to the coloniality of power.

It seems necessary to me to reflect on how the peoples of Mayan roots organized in the EZLN have disarticulated the marriage between revolution and war, which did us so much damage in the immediate past, and obtained such bad results.

It is no longer possible to ignore those who were exterminated in the Central American wars, and how the vanguards repositioned themselves in legality, abandoning the peoples they used (yes, used) for their revolutionary war.

The decision to face peaceful civil resistance to confront the asymmetric war of extermination of the Mexican State is a strategic determination, but it has not the slightest relation to pacifism, if I have understood anything about Zapatismo. It is a reading from below, from the peoples, of the challenges that the system is throwing at us.

This article was published in La Jornada on December 16th, 2022. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/16/opinion/019a1pol English translation bySchools for Chiapas