by Luis Hernández Navarro

“Those who are not afraid, come forward to sign,” said then President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, mimicking the words of Emiliano Zapata, to 268 rural leaders, among them relatives of the Caudillo del Sur (the Caudillo of the South). At Los Pinos, in front of a picture of the head of the Liberating Army (Zapata), the leaders of the national associations went one by one to sign the Peasant Manifesto, which endorsed the end of the agrarian redistribution and the privatization of the ejido (communal land). The date is recorded alongside the ambush at the Hacienda de Chinameca: December 1, 1991.

Before the ceremony began, some of the representatives who caught a whiff of the trap, asked where the bathroom was and beat feet to avoid signing the document. Among them Pancho, a Tseltal leader who spent years fighting for land with his comrades from the Lacandon Jungle. He returned to his region and did not reappear in public life until long after the Zapatista uprising.

The leaders’ pledge to surpass agrarian redististribution by calling for a great effort of compromise among the men of the countryside that day was seen as a great betrayal by hundreds of thousands of peasants throughout the countryside, but especially by the Chiapanecans, who had spent years struggling for their land. This counterreform to Article 27 of the Constitution clouded the indigenous horizon, and motivated hundreds of communities to take up arms.

In the book Voices of History, the inhabitants of Nuevo San Juan Chamula, Nuevo Huixtán, and Nuevo Matzan recall their experience and that of their grandparents on the plantations and in the towns, where they were born and raised enduring hunger, as well as the reasons that led them to colonize the Selva, seeking somewhere to eat a bit better and leave behind the pain of poverty and pure suffering.

Almost everyone we know goes out to the plantation. The landowners have become rich from our work, although we continue to live in poverty. In addition to all the hard work, we have more hardship there. The boss doesn’t care about the workers. We went hungry. The overseers mistreated us a lot: they beat us, they hit us with branches, with belts, with the palm of a machete, they kicked us; they punished us for anything, they explained. That is why, in a modern exodus, they left to seek a new life in the jungle.

The struggle for land became widespread throughout the state during the decades of the 70’s and 80’s. The indigenous people were not only seeking to recover what the landowners had taken through violent dispossession. They had occupied the jungle to flee from misery. A presidential decree from Luis Echeverría Álvare in 1971 granted the possession of 614 thousand hectares to 66 Lacandón families, thereby denying it to the rest of the settlers. In the words of Union of Unions, behind the decree were the interests of National Finance, that is the great bourgeosie, who wanted to take out all of the mahogany and cedar in the thousands of hectares titled in favor of the Lacandón group.

The government wanted to reconcentrate the other indigenous peoples (Tseltales, Tsotsiles, Choles) and fix the limits of the Lacandon Community, by meansthe Brecha (“the gap”). The communities resisted by putting their bodies on the line with the slogan “No to the Brecha! In October 1981, 2,000 peasants from the jungle marched and occupied the Tuxtla Gutierrez plaza. They walked for days to arrive at a vehicle that would take them to the state capitol. Years later, their struggle bore fruit. In 1989, Salinas de Gortari granted the endowment to 26 colonies.

In an interview with Roberto Garduño at La Jornada, the elder Sergio, the Representative (of the community), recalled those operations and how the inhabitants of the region were threatened by the authorities: “With the 1972 decree, the government began to say that we were going to leave by hook or by crook… but we didn’t want to leave because our parents and grandparents sought this place to live and work.”

In the jungle, the rebels learned to handle a rifle to defend themselves against the white guards. Then followed the political and ideological education and the strengthening of communal organization. Sergio recalled the case of coffee sales as a symptom of injustice, because the coyotes cheat and pay ridiculous prices for the product.

“The Zapatistas,” he added, “began to work in our communities house by house and neighborhood by neighborhood. For a long time we struggled peacefully, but they ignored us, that’s why we began… but they didn’t let us, they repressed us, that’s why we took up arms.”

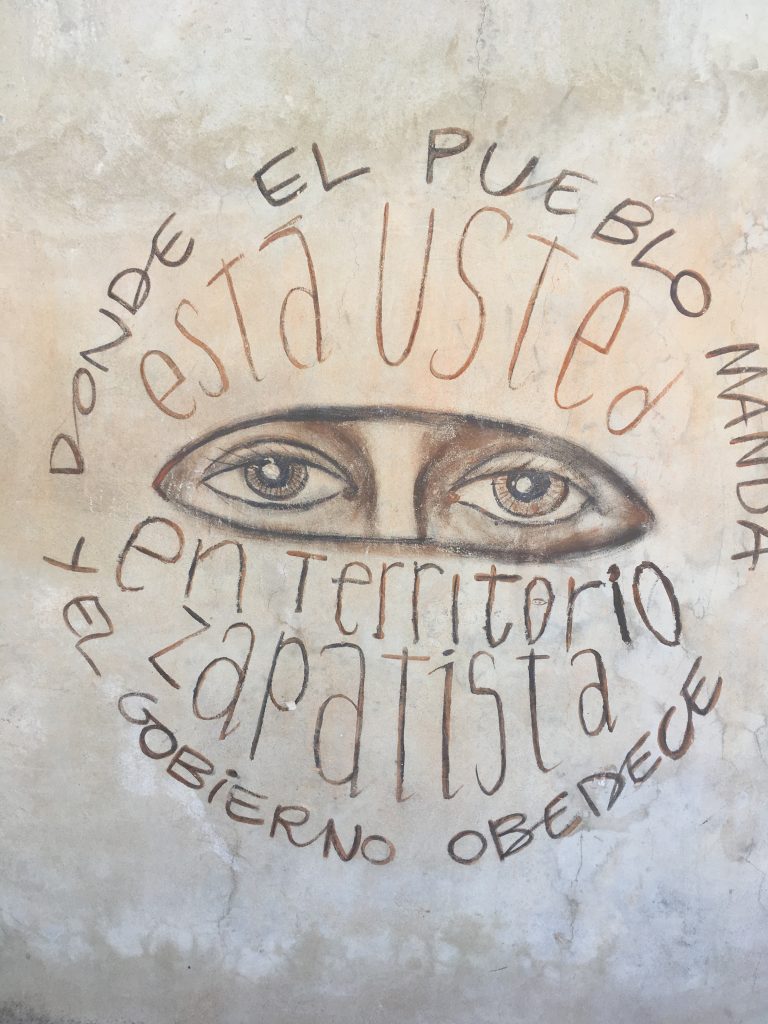

Despite the fact that the white flag had been raised in the countryside, the 1994 uprising allowed peasants and indigenous people, Zapatista and non-Zapatista, to recover thousands of hectares. Instead of parceling them up as others did, the rebels promoted collective organization projects for agricultural and livestock production, which have allowed them to control their lives and practice self-government. These experiences are the material basis on which the Caracoles are built, which this August 9 celebrated their 19th anniversary.

Carlos Salinas’ offense against the small rural producers — when in Los Pinos he called on the leaders to sign without hesitation an agreement to close the door on the peasant way of development–was answered years later by the EZLN, derailing in practice that end to agrarian land redistribution.

But the rebuff went even further. From that initial “no!”, the rebels went on to build a society that represents the opposite of what Salinas wanted to promote. This alternative society has taken shape in the Caracoles. In them is the synthesis of both the deep and subterranean history of peasants and indigenous people for land and autonomy, as well as their willingness and power to build another world.

This article was published in La Jornada on August 9th, 2022. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/09/opinion/016a1pol English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas.